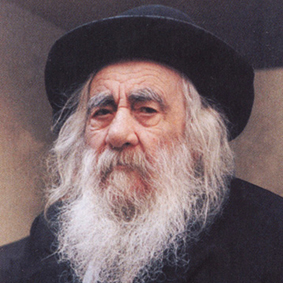

Rav Yaakov Yisroel Kanievsky zt"l

הרב יעקב ישראל בן חיים פרץ קנייבסקי זצ"ל

Av 23 , 5745

Rav Yaakov Yisroel Kanievsky zt"l

The Steipler was born in Hornesteipel in 1899 after his father, Rav Chaim Peretz, a sixty-year-old widower, received a beracha from the Hornesteipel Rebbe, a son-in-law of Rav Chaim of Sanz (Divrei Chaim), that if he remarried he would be zocheh to (merit) a son, after having only daughters. His father was a shochet, a great masmid and yerei shomayim, and his young mother a great Tzaddeikes. Together they had three sons, the oldest being Rav Yaakov Yisrael. In his youth, Rav Yaakov Yisrael contracted life-threatening typhus, and, although he survived, it caused permanent damage to his hearing.

After learning Torah from his father in his early years, at age ten his father sent him to Kremenchug to learn in a Talmud Torah organized by talmidim of Yeshivas Slabodka. A year later, his father was niftar. Yaakov Yisrael was called home to be with his broken mother, but when a contingent from Yeshivas Novardok came to the town to recruit on behalf of the Alter of Novardok, Rav Yosef Yoizel Horowitz, his mother jumped at the opportunity to send her eleven-year-old son away from poverty to a place where he could fulfill his only dream of learning Torah and be provided with food at the same time.

At age nineteen, Rav Yaakov Yisrael was sent to Rogatchov to open a branch in the Novardok network of Yeshivos, which spanned Russia. It was during this time that he was drafted into the Russian Army to fight in the Bolshevik Revolution. Many stories exist regarding his unyielding determination to keep the mitzvos.

After he was freed from the army, the situation in Russia for the Jews deteriorated to the point where talmidim were sneaking across the border on a steady basis. This was a very dangerous undertaking and being caught could be fatal. When Rav Yaakov Yisrael's turn came, they were to be smuggled by a farmer who divided up the group among various family members. Rav Yaakov Yisrael was sent with the farmer’s daughter. Worrying about Yichud (the issur of being alone with her), he ran away, straight into the arms of the Russians. He was jailed but soon managed to escape.

On his next attempt, he needed to stop to relieve himself. Despite the fact that he could have waited until he crossed and his group refused to wait, he broke off from his group and missed his turn, not wanting to violate the aveira of Bal Teshaktzu. During his next attempt, it was Mincha time and he didn't want to miss the Z’man. He went to a quiet place in the forest to daven and spent much time speaking to his Creator, oblivious to the whole world; when he finished, he realized his group had long gone. Lost in the forest, he started wandering until he found himself next to a Bais Medrash. When he asked someone where he was, they told him he was in Slutzk, Poland. He had finally made it across the border!

From there, he went to learn in Bialystok under Rav Avrohom Yoffen, a son-in-law of the Alter. He published his first sefer in 1924, at which point word of his greatness in Torah spread. The Chazon Ish, who was then already in Bnei Brak, suggested Rav Yaakov Yisrael as a match for his sister, after seeing his sefer Shaarei Tvuna that was published in 1925. Indeed, he eventually married her. He then went on to become Rosh Yeshiva in the Novardok branch in Pinsk. In 1934, he moved to Eretz Yisrael and settled in Bnei Brak, the town of his brother-in-law, the Chazon Ish.

The Steipler Gaon spent the rest of his life shunning the limelight, despite being the unofficial successor of his brother-in-law, the Chazon Ish, upon his petira in 1953. He spent most of his time in his modest surroundings learning Torah. Such greatness cannot be kept a secret, however, and an audience with him was priceless for the throngs who came to learn from him, ask him questions, seek his advice and receive his beracha. He was a role model of uncompromising determination in kiyum of each and every one of the Taryag (613) Mitzvos. His Torah is treasured by Bnei Torah across the globe. Most of all, his fiery image and example are forever etched in the forefront of our minds.

The Steipler Gaon returned his holy Neshoma to its Maker on the 23rd of Av, 5745/1985. It is said that 200,000 people attended his Levaya (funeral), the largest ever in Bnei Brak. Yehi Zichro Boruch!

http://revach.net/stories/gedolim-biographies/The-Steipler-Gaon-The-Fiery-Determination-Of-Novhardok/4002

Stories of Rav Yaakov Yisroel Kanievsky zt"l

Rav Ruderman would show talmidim a letter that he received from the Steipler Gaon in 5719 (1959). The Steipler sent him a letter requesting financial assistance for printing the first volume of his magnum opus Kehillas Yaakov. In the letter, the Steipler wrote that he had seen and learned Rav Ruderman’s sefer Avodas HaLevi that he had written in his youth and it features “wonderful chiddushim on the most difficult areas of the order of Kodshim”. In the letter, the Steipler encourages Rav Ruderman to write more such seforim. After showing the letter to the talmid, Rav Ruderman said, “I have enough chiddushim to write ten more volumes of Avodas HaLevi, but I am now writing leibidige seforim, living seforim, my talmidim.”

The Rosh Yeshiva continued, “Teaching takes full concentration, as the Gemora teaches that only if a Rebbe is similar to a Maloch should one seek to learn Torah from him. We know that a Maloch cannot do more than one shelichus, one job at a time. Teaching talmidim preoccupies me so completely that I cannot sit and write seforim.” Indeed, the Rosh Yeshiva invested tremendous effort into teaching and shaping each talmid.

The Rosh Yeshiva established thousands of talmidim. Among them, hundreds became Gedolei Torah and Marbitzei Torah who continue his legacy and illuminate the Torah world with their shiurim and chiddushei Torah. Although of course, there was a special focus on establishing talmidim who would become Torah giants in their own right, the Rosh Yeshiva understood the individual character of each talmid and encouraged them, each in his own way, to make Torah a central part of their lives.

What Does The Steipler Say? was the title of one of the articles eulogizing the Steipler that appeared in the Hebrew Yated (then in its first year of publication) following his petirah. The fact that the question instinctively kept being asked, even though it was no longer possible to consult him, was testimony to the impact of the years of his leadership of the Torah camp.

Fifteen years later, the question essentially still hovers in the air, although there have been vast changes both within our camp and without which necessitate the utmost care in drawing comparisons.

The Chazon Ish was the leader who coordinated the beginnings of the small, weak and struggling new yishuv. He directed its battle to maintain its integrity and its loyalty to Torah in the face of the constant threats of the Zionist establishment to engulf it. His brother-in-law, the Steipler, subsequently tended and guided the flock as it grew in numbers and strength. He warned off attempts to weaken it from within and endeavored to ensure that its voice would be heard in the public forum. He left the Torah community stronger and more self confident than he received it and its growth has boruch Hashem since continued unabated.

Today however, the Torah camp faces unprecedented challenges arising from its own continuing growth and diversification, the ongoing moral decline of the surrounding society and the escalation in the ferocity of the fight against us. Though he can no longer provide direct guidance, the question What would the Steipler say? is still all important. The following selection from the record of his public leadership clearly spells out a distinct message: "Let it be less but let it be pure!"

To Vote or Not to Vote

"Did he sign or didn't he?" -- the question resurfaces before every election. Whether or not to vote and if so, for whom. It is never straightforward. We've chosen the issue of participation in general and municipal elections to begin with, since it illustrates two major features of the Steipler's communal leadership. First, his battle against "the party of deserters" (as he himself called them), namely Po'alei Agudas Yisroel (PAI), and second, the dual leadership which he exercised, together with ylct'a, HaRav Shach. Although these two gedolim did not have frequent contact with each other, their approach to every issue that was brought before them was identical. The way in which each of them submitted to the other's opinions was also remarkable.

"As to the main matter, my humble opinion leans towards the view that it is a great mitzvah to vote for the chareidi list and that this constitutes the saving of religion . . . as for your argument that there are [Torah] prohibitions involved, I have given great consideration as to whether it is worthwhile responding because in truth, it is utterly against my wishes that the members of Neturei Karto, sheyichyu loy't, should change their opinion. Whilst no prohibition is involved in voting, there is zeal for Hashem's sake in their refraining from doing so . . . You wrote that voting involves acknowledging the validity of avoda zorah; however, this is completely unfounded . . . your honor should know that even for zealous ends, it is forbidden to interpret the Torah at variance with halocho, and what is not the truth does not succeed at all."

The contents of this letter (which appears in Karaino De'igarto Vol. I, #203) set guidelines for charting policy in the battle against Zionism through casting votes in elections. That was his approach to the issue; it was a battle whose sole purpose moreover, was to fight the destroyers of religion, not to advance any group's particular interests. He had absolutely no trace whatsoever of party allegiance, which meant that every time a question arose it was judged wholly on its own merits, free from the distorting influence of party interests. On the other hand, neither was there any place for emotional zealotry when it came to determining the halocho and the course of action that arose therefrom.

At that time, the rulings of the Chazon Ish and the Brisker Rov zt'l regarding participation in the elections were being questioned (the questions were actually being fanned by excitability, without checking the facts). The wish to be drawn into the general fight against Zionism gave rise to the inclination to rule out taking any part in the elections and consequently to view the opinions of those gedolim in this light as well. The Steipler and ylct'a, HaRav Shach however, clearly conveyed the message that all that was involved was the battle.

HaRav Shach, before the elections in 5737 (1977): "I am not expressing my own opinions, for this was the view of our master the Chazon Ish, zy'a, and of the Rov of Brisk. They were all of the opinion that one should take part in the elections. If they would have said not to go, I wouldn't go . . . for when we take part in the elections, a voice of protest is heard . . . and I know that the opinion of our master the gaon Rav Yaakov Yisroel Kanievsky . . . is also that one should go . . . I must say further that `they have made me into a liar' when I said that `they were all of the opinion that one should take part.' I know myself that I am not a liar, however, HaRav Kanievsky . . . is certainly not a liar and if he would have heard any hint from the Chazon Ish against taking part, he would not be supporting it now."

The Steipler: "I will just let your honor know that the opinion of the vast majority of gedolei Yisroel approximately twenty years ago was that there is absolutely no trace of issur whatsoever involved, and our master the Chazon Ish ztll'h was among them . . . Regarding the actual question, everyone is obliged to follow the majority opinion in the whole of Torah and in this matter, most of the Torah sages who are with us . . . and who have already departed are [and were] of the opinion that it is a proper obligation . . . As for his advice to write `with the exception of Yerushalayim t'v,' it is utterly unfounded. Is it not enough that I am getting involved in this controversy? Does he want me to become involved in a disagreement about whether the power of the Badatz is only binding upon members of the Eida HaChareidis or all who live in Yerushalayim?" (Karaino De'igarto #154, 156).

This, despite the fact that from another letter his ruling on this point is apparent (K.D. Vol. I #221).

The Battle With PAI

To the same extent that he held it was an obligation to vote in elections, he issued a penetrating ruling that "the party of deserters" should be distanced.

First a word of historical background about the affair. The Po'alei Agudas Yisroel movement was, as its name suggests, originally an organization of chareidi workers. It had been established in Europe under the banner of the Agudas Yisroel World Movement as a counter force to the irreligious Zionist workers' groups. Through its youth movement, part of whose membership was composed of natives of Germany, the movement established a number of settlements in Israel, as needed.

Integration into the country's agricultural life led the movement's leaders to a series of steps that in effect constituted a gradual merger with Zionist organizations. The leaders started to gradually dissociate themselves from the Agudah's Torah leadership, with the process gathering momentum after the State was established.

In 5708 (1948), they planted their settlements on land belonging to the Keren Kayemet Leyisroel (Jewish National Fund), a step that had been debated years earlier with HaRav Elchonon Wassermann zt'l Hy'd, to whom PAI's leaders had replied with a marked lack of respect. Now they tried to attribute their actions to the "silence" (said to equal acquiescence) of the Chazon Ish.

Thereafter, at every issue that arose PAI justified themselves by the fact that they had the consent of gedolei Torah -- who always remained anonymous. So it was with the mixing of boys and girls in the Ezra youth movement; so it was with the negotiations over PAI's participation in Sherut Leumi (national service for girls). Every time there was a different "godol beTorah" who, they said, supported them. (It was concerning their concession to Sherut Leumi that Rav Kalman Kahana, one of the leaders of PAI, received an astounding letter from the Chazon Ish which stated, "a spirit of foolishness possessed you, that you commit suicide . . . " as well as other fearsome remarks.)

In 5711 (1951), elections were held for the mayor of Petach Tikva. The leaders of PAI supported an irreligious candidate, over his opponent who was religious. In a letter from the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah, HaRav Yechezkel Sarna and HaRav Meir Karelitz zt'l forbade this.

HaRav Karelitz (the Chazon Ish's older brother) was then serving as the official rov of the PAI movement. When the politicians stubbornly refused to hearken to this letter, HaRav Karelitz resigned from all positions of rabbinical and any other kind of leadership.

The way things then stood was that on the one hand there was Agudas Yisroel, which remained faithful to the Torah leadership, while on the other was PAI, with its institutions, its settlements and its sources of revenue. All this time, the Agudah's Torah leaders had attempted to bring pressure from the rank and file of PAI members to bear upon the movement's leaders and the two movements still appeared on a joint list for the general elections.

The Rebellion

In the elections of 5720 (1960), the list received six Knesset seats, three of which were allocated to the PAI faction headed by B. Mintz.

Then it happened. The Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah ruled against joining a coalition with the leftist government. However, PAI ignored their ruling and joined. The secular press hailed the move as "PAI's independence day," -- independence that is, from the authority of the Torah leaders.

The response of the Torah community was that leaders, roshei yeshiva and Admorim, gathered to declare that PAI had detached themselves from Agudas Yisroel. The Tchebiner Rov, and the Rebbes of Ger, Vishnitz and Boyan, ruled that their followers must renounce their membership of PAI, even if their livelihoods would suffer as a consequence. Thereafter, Agudas Yisroel and PAI ran for the Knesset on separate lists.

In 5733 (1973), Rabbi Y. M. Levin z'l who served as chairman of the Agudah's central committee, passed away. He had always worked to preserve the movement's unity. After he had been replaced, new winds began to blow within Agudas Yisroel itself, calling for PAI's return to the Knesset list. In view of the approaching elections, a meeting of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah was convened (on very short notice and including rabbonim who had not hitherto sat on the Moetzes). The Steipler sent a letter to HaRav Shach, part of which read, "regarding the rumor that Agudas Yisroel is considering reuniting with the deserters, who call themselves PAI, who have made a public disgrace of themselves on more than one occasion, and whose ideology is the idol of Zionism, and of `my strength and the power of my hand', R'l, and who without a doubt would be prepared even now to go immediately against the Aguda and the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah if only they imagined that they would have some political or material gain by so doing -- in my humble opinion, it is clear that merging with them would be a dreadful chillul Hashem, for it would be interpreted as a de facto approval of all their scheming and [would show] that insolence against Torah and against the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah reaps handsome benefits. Please . . . do everything possible to prevent merging with them . . . it is clear, in my humble opinion, that if Agudas Yisroel does merge with them, that very many members will distance themselves, whose only connection with the Aguda at present lies in the fact that it is not together with `the other side.' "

At the meeting of the Moetzes, HaRav Shach arose and read out the Steipler's letter. One of the politicians who was among those invited, and who was in favor of the merger reacted by proposing "that we put it to a vote." Most of the members (including the new ones) supported the merger, with the result of which was called "the United Torah Front."

HaRav Shach announced immediately that he was resigning his membership in the Moetzes. HaRav Shlomo Berman, who was a member of the presidium of Agudas Yisroel, also resigned in protest at the way things had been arranged. During the pre- election campaigning the signatures of these and of other gedolei Torah did not appear in support of Agudas Yisroel. However, since there was no alternative chareidi list, no actual opposition was voiced.

Rabbi Shlomo Lorincz, who was faithful to the instructions of the gedolei Torah and who was the first candidate on the Aguda list, was instructed not to resign, but to refrain from making speeches in Yerushalayim and Bnei Brak in support of the Aguda list. (He was permitted to speak on the Agudah's behalf in outlying communities, for if the chareidi Jews who lived there did not vote for Agudas Yisroel, their connection with the chareidi organization could be lost.)

An avreich who asked about voting was told, "This time there's no order to vote, and when you're not ordered to, you don't vote."

In that election, the combined list won five seats, which represented the loss of a seat, since before the two parties had always won six.

The Trend Reversed

In 5737 (1977), the Gerrer Rebbe, the Beis Yisroel, instructed the party workers to run on a separate list from PAI, in order to unite the chareidim once again and to obtain HaRav Shach's consent to return to the Moetzes. HaRav Shach did so and issued an appeal to vote in the elections. The Steipler added his own letter of warm support, which he closed with the following lines, "And this has already been publicized and articulated well by . . . the gaon and tzaddik, from the remnants of the Knesses Hagedola, the truly mighty Torah scholars, his honor . . . HaRav Eliezer Menachem Shach."

In that election Agudas Yisroel maintained its strength while PAI won only one seat.

The trouble erupted again just a year later, when municipal elections were held in Bnei Brak. A joint list was prepared and it was headed by a PAI candidate. The fact that just a year had passed since PAI had been ejected from Agudas Yisroel and already a way had been found for them to sneak back inside, and in Bnei Brak too, evoked a strong response from the gedolei Torah. The Steipler and ylct'a, HaRav Shach, bade HaRav Chaim Shaul Karelitz to issue a notice conveying their instructions not to vote for the Aguda list.

Some argued that this directive was only intended for bnei Torah themselves, but that their families and those who were not bnei Torah could vote, and this led to an interesting episode. After tefillah in the Lederman beis haknesses, HaRav Chaim Kanievsky went over to the notice board and added, in his own hand, the following words to HaRav Karelitz's note: Both talmidei chachomim and amei ho'oretz, they themselves and their wives, their sons and their daughters.

Before the 5741 (1981) elections, Aguda activists approached the Steipler for a letter of support but he dismissed them and did not grant their request. Rav E. Tabaschnik, who used to frequent the Steipler's home, heard from him at that time that he was displeased at the situation inside Agudas Yisroel and that he did not intend to sign for them at all. However just a few days later, a letter signed by the Steipler appeared, calling upon voters to vote for the Aguda, albeit phrased in somewhat reserved terms.

Rav Tabaschnik took himself off to the Steipler's home to find out what had brought about the change of heart. When he entered the Steipler said to him, "I told you that I wasn't going to write but I heard that HaRav Shach was upset by that, so I agreed to write."

Three days later, it was publicized that the [separate] PAI list had been strengthened from within Agudas Yisroel and the Steipler hurried to write a second letter that added, "I now add that in view of this, every vote for a different list literally constitutes demolition and destruction for Jewry, and whoever votes for a different list is among those who leads the public to sin, R'l."

In those elections PAI disappeared from the political map, receiving fewer than the minimum number of votes required for one seat and the movement has only declined since.

Girls' Conscription and Sherut Leumi

In 5731 (1971), the Steipler was shown an item in the journal Hapeles which stated that the Israeli government had plans to reintroduce legislation making Sherut Leumi (national service, to parallel army service) compulsory for all girls. The Steipler immediately wrote to one of the rabbonim in America, "Please, have mercy on us, on Jewry, and do anything that you find can to be of any help in effecting a rescue. I don't know how, maybe by sending an influential delegation to the Consul, maybe through an article in a newspaper with wide circulation, to beg for mercy, that the blood of shomrei Torah umitzvos should not be shed, to have their daughters slaughtered before their eyes R'l . . . "

This letter made a deep impression and the recipient passed it on to a friend of his who asked the Steipler for permission to circulate it in the botei medrash. The Steipler replied, "The matter needs to be reflected on, because I think that my choice of words implied that I was testifying that they are planning to issue a decree etc. whereas, regarding the facts, I am a dweller of tents who knows nothing of what happens beyond what others tell me. Last year they told me that there was some plan to make the above decree and then they told me that all they wanted was to ensure that irreligious girls would be unable to resort to trickery and present themselves as religious. However, I didn't know what the true facts were. I wrote my letter to the above rov in response to an article which I was shown in Hapeles of erev Shavuos . . . where everything which I wrote about appeared. I was aghast, for it appeared that the decree was very close at hand chas vesholom, and that nobody was taking action to prevent it, may Hashem yisborach have mercy. At any rate, it did not occur to me that my letter would be so widely publicized, for when something is to be made public it is imperative to take great care over how it is phrased and the source [of the information] should have been brought, rather than giving the appearance of my testifying about it."

Two days later, the Steipler addressed another letter to the same person. "Regarding my letter of two days ago, now there is an ongoing rumor to the effect that the danger of the evil decree is very great, and I repeat my request and cast my supplication: please, make every possible effort in any direction that you judge might be helpful. You can do whatever you see fit with the letter that I wrote to the rov, shlita."

In 5732 (1972), the law of compulsory national service for girls was reintroduced with added vigor, and the Steipler was again active. Originally, he formulated the following letter: "Concerning the rumor that has come to pass . . . this dreadful decree hovered over us twenty years ago . . . and all the gedolei hador, the mighty Torah scholars who were then alive, trembled and raised a commotion over it and ruled that it was a stringent and fearsome prohibition in any form . . . and all because it is an accessory of immorality, R'l . . . We feel obliged to make it publicly known that this prohibition against conscripting girls, in any way or form whatsoever, is still fully in force, with renewed vigor, for the burim are slipping lower and none come to ask . . . "

This was the letter which he originally intended to publish. However, he eventually decided that he preferred to publish the original ruling of HaRav Tzvi Pesach Frank, HaRav Isser Zalman Meltzer, HaRav Zelig Reuven Bengis and the Tchebiner Rov, and to add a few lines explaining why the ruling was being publicized, that would make it clear that it was still in force. He then decided that his opinion that the original ruling still applied should appear explicitly and when that had been prepared, he asked that HaRav Shach add his signature so that it would be clear that they both concurred in this ruling.

The announcement was signed in this form on the twentieth of Cheshvan 5732. Two days later, it was decided that the letter should be sent to the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of Agudas Yisroel and, after a slight amendment had been made, it was signed by four of the members of that body (including of course, HaRav Shach). However, since the Steipler was not a member of the Moetzes, his signature was omitted from that letter. It appeared on a second version, which was printed separately alongside the other one.

A month later, an additional letter signed by the Steipler and ylct'a, HaRav Shach was sent to the British Chief Rabbi, asking him to intervene.

The Bnei Yisrael Of India

When the question of the lineage of the Indian tribe known as Bnei Yisrael arose, the Israeli Chief Rabbinate (at the prompting of the Ministry of Religions), leaned towards declaring them fit to marry Jews. The Steipler spoke up to oppose this ruling and he and ylct'a, HaRav Shach, published a letter: "Our opinion is that since they have already been forbidden by our teachers, the gedolim of Bovel and Yerushalayim, ir hakodesh, ever since the question arose a century ago and their prohibition spread to all the botei din that had to consider the matter, the prohibition is in full force and they remain forbidden."

In further letters to a meeting of rabbonim which convened on the matter, the Steipler wrote, "It is imperative to turn to all Torah scholars, gedolei Yisroel, the generation's geonim . . . to make a permanent enactment, until the arrival of the Redeemer, that anyone who wishes to marry must first of all prove beyond question that his ancestry is neither chas vesholom from those families, nor from others who have become mixed with them."

The strong opposition prevented those in power from implementing their plan. The Minister of Religions at the time was Dr. Zerach Warhaftig (NRP). When he heard about how fierce the opposition was, he asked for a meeting to be arranged between himself and the Steipler. One day he knocked on the Steipler's door, accompanied by his entourage. When the Steipler was informed who had come, he refused to receive him, explaining, "Whatever I say to him, he'll repeat the opposite in my name and he'll turn my words around to suit himself."

After a number of emissaries had been sent to entreat the Steipler to grant the meeting, he agreed to receive the visitor but said that he would not reply to him on the subject. The Minister entered and asked, "Are they forbidden to marry Jews?"

The Steipler answered, "I don't want to reply."

The Minister asked, "Must I instruct rabbonim not to arrange weddings for them?"

The Steipler answered, "I don't want to reply," and then he said, "This I ask of you -- don't persecute those rabbonim who don't arrange weddings for them. However, I don't want to speak about the actual question itself."

The Minister left the house and was heard saying to the members of his group, "The Rav said that I don't need to instruct the rabbonim not to arrange weddings." The next day, the NRP's newspaper Hatsofe printed the "news" that the Steipler had ruled thus for the Minister Dr. Warhaftig on the latter's visit to his home.

When the Steipler was told about this, he rushed to issue a contradiction. "I have been told that in this Wednesday's edition of Hatsofe it was written that the Doctor quoted me as having said that a rav who permits marriage with one of the tribe known as Bnei Yisrael is allowed to marry the couple but that no pressure should be brought to bear on those who think that it is forbidden. This is utterly incorrect. I never said that a rav who permits it may chas vesholom do so. Only, because it was clear that they wouldn't listen to me at all [if I would have told them] to cancel the hetter, I asked that at any rate, as a small concession, not to pressure those rabbonim who do not wish to deal with it. I said this explicitly so that it shouldn't be interpreted as though there are any grounds for permitting it . . . " (Based on an eyewitness account).

In this connection, it is worthwhile relating something which the Steipler said the Brisker Rov told him, as an example of the great care necessary when giving halachic rulings. When the "national home" was declared (the Balfour Declaration), people came to ask the Rov if Hallel should be said. He answered, "What does Hallel have to do with this issue? If you had asked about shehecheyonu, that would be more understandable . . . " The questioners went away and then said that the Brisker Rov had said that the brocho of shehecheyonu should be made.

Everyone has his own portrait of each Godol he has encountered. The following story of Rav Yaakov Yisrael Kanievsky, the Steipler Gaon, is what comes to mind every time his name is mentioned. When he was drafted into the Russian Army and Shabbos approached, he marched right into his commander's office and let it be known that he would not be Mechallel Shabbos. The officer was so taken aback by the unprecedented chutzpa and suicidal gambit of this new recruit that he said he would allow him to keep Shabbos if he agreed to one condition. In a continuation of his stubbornness, the Steipler said he did not even have to tell him what he had in mind because – yes, he agreed.

“Okay,” said the officer. “In that case, since you will give more work to your co-soldiers, they will have the privilege of beating you to their hearts’ content.” Despite knowing the viciousness of these strong young men and their anti-Semitism, the Steipler not only happily accepted this savage near-death beating but he said that he carried these special moments with him for the rest of his life and was never able to do anything that could recapture or repeat the life that it pumped into his broken body. This was the way the Steipler approached every mitzva opportunity, Kala K'Chamura (easy or difficult).

One year, a Talmid Chochom in Bnei Brak was niftar before Purim. Shortly thereafter, one of the Steipler’s close students came to see him to discuss a matter concerning the almona (widow) of the Talmid Chochom who had passed away. In the midst of the conversation, the Steipler said suddenly, “Pesach is approaching. The almona will sit down the night of the Seder and be pained by her loneliness. She will remember that her husband always ate hand matza the night of the Seder, but most probably she would not have bought hand matza. I’ll give some of my matza to her.” The Steipler got up and took out his package of matza, giving some to his student. He said, “There’s enough here for the night of the Seder. When you give her the matza, don’t say that I sent it to her, because it’s forbidden to give a present to a woman. Simply say that I gave you this matza to give over to someone who needs it.”

The talmid later said, “It’s impossible to describe in words the incredible excitement and tears in the house of the almona when I entered and said to her, “I have matza for you from the Steipler for the night of the Seder.” (Chaim Sheyesh Bohem: Halichos Vehanhogos)

http://revach.net/stories/story-corner/The-Steiplers-Matza-for-The-Seder/2129

The Rema paskens (OC 551:2) that the issur of building and planting in the three weeks and even during the nine days does not apply if it is for a Mitzva. The Mishna Berura (14) says that if someone does not yet have children and is scheduled to get married after Tisha B'Av, they may buy clothing for the wedding even in the nine days.

The Piskei Teshuvos (10) says that based on this halocha, you may buy seforim in the nine days if you need the sefer to learn from. However, he mentions that the Steipler Gaon (Orchos Rabbeinu) was machmir not to allow new seforim into his home in the three weeks.

One time, when a box of seforim arrived during the nine days, he instructed his family members not to open it until after Tisha B'Av. So great was his simcha in learning new seforim that he was makpid for himself, since for him it was a much too joyous event.

http://revach.net/halacha/tshuvos/Steipler-Gaon-Buying-Seforim-In-The-Three-Weeks/4631

The Steipler Gaon was especially makpid on Kevod HaSefer. The sefer Toldos Yaakov gives some examples of his diligence and sensitivity in his Kevod HaSefer.

• Once, when someone took out the wrong sefer for him, before returning it to its place on the shelf he made sure to learn something from it in order not to “embarrass” it.

• He would fix every rip in his seforim. When he rebound his Shas he said, “I have pleasure from the fact that my seforim have been restored with their proper honor.”

• If he fell asleep on a sefer after learning until his last ounce of energy dissipated, he would feel terrible about the lack of kovod for the sefer.

• Two of his seforim, Birchas Peretz and Chayei Olam, were originally sold at cost price because he felt they were worthwhile to disseminate publicly. Afterward, he decided to raise the price because he felt it was not kovod for the seforim to be sold so inexpensively. The profits were given to Tzedoka.

In many shuls and Yeshivos in Eretz Yisrael, there is a letter hung near the seforim shelves regarding the importance of returning seforim after using them and not leaving them on the table. It tells a story of a time that the Steipler Gaon finished learning in a Yeshiva not far from his home. After walking approximately a hundred meters, despite the fact that walking was very difficult for him, he realized that he had not returned his sefer to its place. He then turned around, went back to the place he was sitting, replaced the sefer – and only then went home.

The Steipler Gaon was a living Sefer Torah. We may never reach his level of Torah but there is no reason we cannot reach his level of respect for the seforim in which the Torah is written.