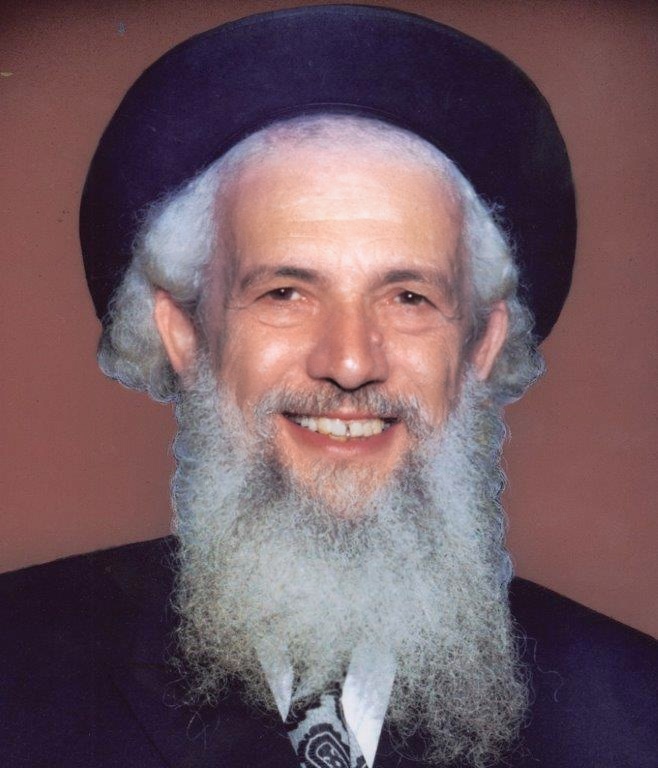

Rav Gedalia Schorr zt"l

הרב גדליה בן אברהם שור זצ"ל

Tammuz 7 , 5739

Rav Gedalia Schorr zt"l

Rav Gedaliah HaLevi Schorr zt”l was born on November 27, 1910 (25 Cheshvan, 5671) in Istrik, a village near the town of Pshemishel, Galicia, to Rav Avrohom and Mattel Schorr. When he was 12 years old, his family moved to America, where they lived on the Lower East Side. He learned with tremendous hasmadah, often through the night, while mastering many mesechtos during this period. At the young age of fifteen, he began saying a shiur in Daf Yomi, and finished Shas twice before his wedding. He also met many of the Gedolei Torah who visited America to raise funds for their yeshivos, including Rav Meir Shapiro of Lublin, Rav Elchonon Wasserman of Baranowitz, and Rav Aharon Kotler of Kletzk. Rav Meir Shapiro is reported to have stated that Rav Gedalya Schorr was the greatest mind he met in America, and one of the greatest in the world. Rav Gedaliah joined Yeshiva Torah Vodaath when his family moved to Williamsburg. He quickly became the heart and soul of the Bais Medrash, where his brilliant “kushyos” generated excitement with regard to the sugyos the Yeshiva was learning. When he was twenty one years old, Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz appointed him to a position in the Mesivta, despite his unmarried status. His talmidim, many were only a few years his junior, were drawn to him, and accorded him great respect. In 1938, he married Rebbetzen Shifra Isbee, and set sail for Europe to learn by Rav Aharon Kotler in Kletzk, Poland. He learned in Kletzk for two zemanim, until the outbreak of WWII. During that time, he spent his Pesach Bain Hazemanim with Rav Moshenu of Boyan. He also visited Rav Chaim Ozer Grozinsky, the Rav of Vilna, who gave him an inscribed volume of his recently published Achiezer. Upon his return to America, he once again assumed his position as a Magid Shiur in Torah Vodaath, but also spent a great deal of time raising money and securing visas to save his brethren who were left in Europe. Nothing stood in his way; he even sold his own beloved Vilna Shas, and donated the proceeds to the Vaad Hatzalah. In 1947, Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz transferred the Hanhalla of the Yeshiva to Rav Schorr and Rav Yaakov Kaminetzky. Rav Schorr spent a great deal of time ensuring that each talmid find his proper place in a shiur that would best suit his needs. On occasion, he would gather some bochurim for a shiur in his office. Rav Schorr would give extra shiurim in additional perakim of the mesechta that were being learned in the yeshiva, as well as saying daily shiurim in Chumash with Ramban and other seforim. Rav Schorr also delivered shmuezin for the Bais Medrash, where he would weave together the words of many sources to illuminate a clear understanding of the Parshah. In his shmuezin, he would often quote the Ramban, Maharal, Kuzari, Sfas Emes, Reb Tzadok, Shem MiShmuel and many other sources. His legendary talks before the Yomim Tovim would uplift the talmidim, giving them an elevated awareness of the upcoming Yom Tov. These Shmuezen were printed posthumously in his Sefer Ohr Gedalyahu, which has become a classic text on the Parshiyos and the chaggim. In 1958, Rav Schorr began saying shiurim in Bais Medrash Elyon. He would travel by bus to Monsey on Wednesday evenings to say the Shiur Klali the next morning, followed by a 1 shmuez in the afternoon, before returning to New York. In 1960, Rav Schorr established the Kollel in Torah Vodaath, with the financial responsibility resting squarely on his shoulders, despite his being uncomfortable in the fundraising role. On 7 Tamuz 5739, after speaking at the Sheva Brachos of a talmid, he returned his lofty soul to Hashem. America had lost what Rav Aharon Kotler called “the first American Gadol”, yet his teachings continue on through his Sefer Ohr Gedalyahu, and in the multitude of talmidim that he taught for nearly half a century.

He passed away on Monday, 7 Tammuz תשלט and was laid to rest on Har Hazeisim near the tziyun of Rav Mordechai Shlomo of Boyan.

Stories of Rav Gedalia Schorr zt"l

By Rabbi Nosson Scherman

(This article originally appeared in the Jewish Observer and is available by ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications ~ Matzav.com)

The last day of Rav Gedalia Schorr’s life was typical of so many others, especially in his later years. It should have been a quieter day than most. The official Yeshiva school year was over. Nonetheless, Rav Schorr had gone to the Yeshiva to arrange personal favors for a few of the young people under his care. Such private favors were an essential part of his life; they had always been a major component of his broad definition of his duties and responsibilities, both as a Jew and as a Rosh Yeshiva. While there, he became engaged in an impromptu discussion that involved another of those duties and responsibilities.

Someone had sharply criticized another person. The Rosh Yeshiva responded with the calm and good humor that were his trademarks. The conversation was not pleasant; he maintained his composure with difficulty, but would not permit another human being’s worth to be dragged down. Such experiences were especially taxing for him, because of the nature of the discussion and because it was characteristic of him to recognize the justice on both sides of a seemingly unbridgeable chasm. The person he defended that Sunday would never learn what had happened. Rav Schorr never told people what he had done for them, because they would have been embarrassed, and because he understood helping a fellow Jew as an obligation to Hashem, not as a means of accumulating the IOUs on which power is built. Other Yeshiva matters were brought up, and then he left for the day.

Tomorrow would have been another day; in fact, it might well have become a historic one for Torah institutions throughout the metropolitan area. Rav Schorr had become the acknowledged leader and principal spokesman for Yeshivos in a new initiative with the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies of New York, which, if successful, could have resulted in a major victory in the constant struggle to stave off financial catastrophe for Torah education. For the next day he had called a meeting of representatives of major Yeshivos with Federation officials. It was not his style to call meetings, but these institutions looked to him as the ones that could best represent them. In his quiet, unassuming way – and with the characteristic shrug that said, “Couldn’t you find someone better?” he acceded. In an informal meeting on the issue with a Federation leader, his combination of Torah aristocracy, passionate sincerity, gentle wit and winning personality had achieved a significant breakthrough. Another meeting with another key leader was to be arranged later in the week.

But that Yeshiva meeting would be the next day. That night – Sunday evening, the 7th of Tammuz, 5739/July, 1979 – he would be at the Sheva Berochos of a talmid and his bride.

Rav Schorr was asked to speak. The aggravation of the day and the tension of the morrow disappeared from his consciousness as he immersed himself in the world he knew and loved best – the world of Torah. The riches of his vast treasury of knowledge would be culled for appropriate verses, passages and thoughts. Some famous speakers captivate the majority of their audiences, but generally, the greater the scholarship of an individual listener, the more unimpressed, even bored, he will be. With Rav Schorr the opposite was true. So quick were his thoughts, so profound his insights, so complex his tapestry, so original his ideas, so well-documented his references, so wide-ranging his allusions, that only the most learned of his listeners could truly comprehend and fully appreciate his mastery of content.

At this particular Sheva Berochos, most of his listeners were Polish Chassidim of scholarly background. They could appreciate better than most his command of Sfas Emes, Rav Tzodok of Lublin, Maharal and the other masters whose thoughts Rav Schorr expounded and interpreted in a manner both unique and awe-inspiring. A few days before, he had spoken at the bris mila of the infant son of a former talmid, now a prominent Yeshiva educator. Then, his most enthralled and admiring listener had been a senior Rosh Yeshiva in one of America’s most distinguished Lithuanian-type Yeshivos. That Rosh Yeshiva, a distinguished European Talmid Chochom and exponent of Mussar, unabashedly expressed his esteem for the American-trained Rav Schorr.

He spoke, as he always did, with his head cocked slightly to one side and his eyes closed. He seemed to shut out the world. He was communicating Hashem’s Torah; the orator’s techniques – eye contact, voice modulation, dramatic effects – held no interest for him. He was thinking as he spoke because his brilliant mind was never at rest, adding asides and new flashes of insight. Though he eschewed rhetoric, the beauty of his thought would frequently find expression in felicity of phrase. As he spoke then, he smiled and said that forgiveness of sins on the wedding day is Hashem’s derosha geshank (gift) to chosson and kalla.

Delivering both these talks, at the bris and at the Sheva Berochos, must have been difficult, for he had not been well either day. But his listeners detected no weakness either time. Torah was his life, and gave him vigor. Perhaps that youthful exhilaration was Hashem’s gift to him, in return for the pride, glory and growth he gave the cause of Torah in this New World where people said it could never take root.

He finished his talk and sat down. The fatigue showed. The Polish-bred Rosh Yeshiva next to him expressed appreciation. A former talmid and current friend (Rav Schorr never learned to keep people at the arm’s length that engenders awe) approached smilingly with hand extended. He had left the Bais Medrash of Torah Vodaas over twenty-five years earlier, and was now a grandfather. He shook hands with his Rebbe and said, “When I hear you speak it reminds me of my Yeshiva days.” Rav Schorr smiled and said, “Takeh, takeh, emes.” (Indeed, indeed. True.)

His head then fell forward. The American Torah world had lost its greatest product. World Jewry had lost one of its greatest, most well-rounded Gedolim. And the still-unfinished process would begin of attempting to reveal the true picture of a man who devoted much of his genius to concealing his greatness from even his closest intimates.

Rav Gedalia Schorr was born to Rav Avrohom HaLevi Schorr and his wife in Istrick, a Galician shtetl near Pszemiszl, in Cheshvan 5671(1910). They named him after his paternal grandfather, Gedalia, a highly respected Talmid Chochom and close Chassid of the Sadigerer Rebbe, grandson of the holy Rav Yisrael of Rizhin. Like his father and grandfather, the young Gedalia became a diligent scholar and devout Chassid. The Schorr family came to America when he was twelve years old, settling first on the Lower East Side and then moving to Williamsburg. Rav Gedalia dedicated himself to learning with a passion that he maintained throughout his life.

On the fast of the 17th of Tammuz, when he was fifteen, he learned through the entire Masseches Sukka, not leaving his Gemora from morning until Maariv. For a period of over a year, he remained in an upstairs room of the family home, studying Torah without interruption. His mother, always solicitous of his study, brought him his meals. He completed several tractates that year, but he would not discuss details. From the time he reached his middle teens, it was his practice to study all through Thursday night and Friday, deliver a shiur after the evening meal to fellow mispallelim at the Zeirei Agudas Yisrael of Williamsburg, and only then go to sleep.

Word spread that in America a youngster was developing into a Torah giant of European proportions. That was astonishing and inspiring for a country where one could count the high school-level Yeshivos on the fingers of one hand and still have fingers to spare. The revered Rav of Lublin, Rav Meir Shapiro, spent many months in the United States when Rav Schorr was not yet twenty. As was his wont, the Lubliner Rav sought out promising young men and discussed their studies with them. Of the young Gedalia Schorr he said, “He has the most brilliant mind I have come across in America, and one of the most brilliant in the world.”

During those formative years, he developed the all-embracing range of Torah knowledge that was almost uniquely his. His lightning grasp and incisive comprehension were complemented by a phenomenal memory. Shortly before his passing, he remarked in a casual conversation to a nephew that he had not seen a certain sefer since he had learned it through at the age of nineteen. He then proceeded to quote from it as though he had seen it only yesterday. That sort of intellectual brilliance is the bane of many a genius; things come so easily to them that they seldom use their full potential. But, although he grew up at a time when the American Yeshivos offered little stimulating competition, Rav Schorr was driven by a relentless desire to achieve Torah greatness. His mind was inquisitive, voracious and fresh.

Always ready to praise others, pinpointing their precise area of excellence, he once said of someone, “He has the unusual ability to look at a passage of Talmud as though he had never seen it before; his approach is never stale.” The same thing might have been said of himself.

Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz, Menahel of Torah Vodaas and the prime architect of the Yeshiva movement in America, looked to Rav Schorr as his own successor and as one of the leaders of the next generation.

When Rav Schorr was only twenty-one years old, Rav Mendlowitz appointed him to conduct the highest shiur in Mesivta Torah Vodaas. In later years, when Rav Shlomo Heiman, Rosh Yeshiva of Torah Vodaas, became ill and was unable to carry on his duties for a year and a half, Rav Shlomo asked that Rav Schorr replace him for the duration of the illness. Those were the years when heads would turn in Williamsburg at the sight of a tall, handsome, youthful man striding energetically down the street surrounded by others barely his junior who addressed him as Rebbe, while peppering him with questions on the day’s shiur.

Despite his scholastic achievements and the awe in which he was held by people two generations older, he was never a cloistered, other-worldly figure.

In Williamsburg, like in other American Jewish communities of yesteryear, most Jews confined Shabbos to the mothballs with the other family heirlooms. Rav Schorr and another young man would prepare makeshift platforms of milk boxes or garbage cans on Friday afternoons at the corner of Lee Avenue and Hewes Street. On Shabbos, Rav Schorr would mount the platform and speak in Yiddish on behalf of the holy Shabbos, followed by his colleague, who spoke in English.

Although Rav Schorr was the teacher, acknowledged Talmid Chochom and prime spiritual force of the Williamsburg Zeirei during those years, he was not above sweeping and mopping the shul on Friday afternoons when it was his turn. And when Rav Shlomo Heiman was coming to America with his Rebbetzin to become Rosh Yeshiva of Torah Vodaas, Rav Mendlowitz assigned Rav Schorr the task of finding and furnishing a suitable apartment for them.

In the 1930s, Rav Schorr had reached the virtual zenith of his profession. Still in his twenties, he was a leading Rosh Yeshiva in the western hemisphere’s premier Torah institution. But that sort of “making it” was not his goal. His definition of success was constant striving to grow in Torah and fear of Hashem. He had met many European Roshei Yeshiva who had been forced to raise funds in America for their impoverished institutions and destitute students, heard their lectures, and spoken with them; but he was most attracted to Rav Aharon Kotler. Soon after his marriage to Shifra Isbee in 1938, Rav Schorr left Torah Vodaas, accompanied by his wife, to study in Kletzk under Rav Aharon.

By the standards of Kletzk, without indoor plumbing and other rudimentary necessities of any American hovel, the Schorrs were well-to-do. Rebbetzin Schorr had to use water pumped from an outdoor well like everyone else, but at least she and her husband had mattresses to sleep on! To his distress, Rav Schorr discovered that the family of his Rebbe, Rav Aharon, slept on straw. That, the young Rosh Yeshiva - turned-student could not tolerate, so he dipped into his meager savings to purchase mattresses for Rav Aharon and the Rebbetzin. For the rest of his life, Rav Schorr considered Rav Aharon his Rebbe. On his desk at home, he kept Rav Aharon’s picture. During 1940, when the Kletzker Rosh Yeshiva was making his way through Siberia to Japan and finally to the United States, he corresponded with Rav Schorr, relying on him to secure visas, papers and tickets for his arrival in America. The letters and documents of those harrowing months are still in the possession of the Schorr family.

Rav Aharon had described Rav Schorr as the first American Godol, and it was not an empty appellation. He respected him and consulted him. Once Rav Aharon suffered severe intestinal pain and consulted three well-known specialists. Upon returning home from the last doctor, while taking off his hat and coat, he said to the confidant who had arranged the appointments, “Call Rav Schorr, I must discuss this with him. Er hot nit nor a gutte kop, nor a glatte kop – Not only does he have a good head, but he has a clear, logical mind.”

During the Sukkos and Pesach that he spent in Europe, Rav Schorr experienced his family’s Chassidic roots. He spent one Pesach Seder at the table of Rav Moshe’nyu Boyaner of Cracow, a scion of the Rizhiner dynasty. He was a widely renowned Talmid Chochom; Chassidim came to him as a Rebbe and Misnagdim came to him for his Torah. Rav Schorr was deeply moved by that Seder; undoubtedly it influenced his own family Sedorim, occasions that formed indelible memories of seriousness, joy and uplift to all who were present.

He met his relatives in little Istrick, among them his mother’s brother Yitzchok, who was niftar later that year and whom he described as an unusual Gaon. He heard more about a Dayan of whom his mother had spoken, a man who had written a brilliant commentary on K’tzos HaChoshen, and of whom it was said, “When he serves as town Dayan, no one can believe he is a Chassid; and when he sits humbly at his Rebbe’s tisch in Chortkov, no one can believe he is a great Talmid Chochom.” Perhaps Rav Schorr was inspired by that description; certainly it could have been applied to him as well.

Powerful influences came to play on him that year. They reinforced his convictions and aspirations: there must be an uncompromising dedication to rigorous growth in Torah scholarship; public acclaim is a dangerous chimera that can impede, but never advance one’s personal growth; a moment is too precious to waste; each fellow Jew is part of one’s own being and destiny. His road toward Hashem’s service had been charted by Rav Aharon and by the Rizhiner Chassidus, particularly its Sadigura branch.

When the war broke out, Rav Schorr returned to his teaching position in Torah Vodaas and simultaneously began a parallel chapter of his life. Europe’s Jewry was on the brink of destruction, while in America little was being done to save it. The Williamsburg Zeirei at 616 Bedford Avenue became a beehive of hatzola work. Funds, food packages, immigration affidavits, intervention with Washington – every possible avenue was pursued, and thousands of lives were saved, thanks to the work of the idealistic, unselfish young activists of 616. The leader of the hatzola work was Reb Elimelech “Mike” Tress; and the spiritual leader of the Zeirei, and of Mike, was Rav Schorr. Close friends, they gave one another inspiration and support, each in his own way.

Scores of people still remember the Shabbos when Rav Schorr received a report about exterminations and the need for rescue efforts. He spoke to the minyan during the services until every single person there was weeping, and determined to give first priority to rescue work. On a sub-freezing January Shabbos he walked from Williamsburg to Boro Park to make an appeal. He arrived, numb and frozen – but the freezing in the ghettos was worse, so he came. He owned one personal treasure: a Vilna Shas that he had purchased in Europe several years earlier. He sold it for $80, which he contributed to the rescue effort.

In later years, he refused to discuss his wartime hatzola work. To the pleadings of his children to tell them, he would reply as he did to similar requests, “The Rizhiner used to say that Hashem is zochair nishkochos – He remembers what is forgotten; He remembers what we forget. If we forget our sins, as though they had never occurred, He will remember them. If we forget the bit of good we have done and think instead of how we must still perfect ourselves, He will remember our accomplishments. What is remembered below is forgotten Above. What is forgotten below is remembered Above.”

Rav Schorr combined compassion for the suffering of an individual with a strong sense of community, not simply as a matter of extended sensitivity or warm emotions, but rather from a fully rounded conception of the Torah’s demands upon him as a Jew, as teacher, leader, husband, father, and member of Klal Yisrael. He acted as a Jew fulfilling Hashem’s mission to serve others – with or without their request or even their knowledge, helping even those who had abused his friendship and good nature.

As teacher, Rav Schorr went with impoverished students to purchase Pesach outfits for them. He often expressed surprised disappointment at the idea that a Rebbe had no obligation to tend to the personal needs of his students.

Twenty-eight years before his passing, he secretly arranged for a successful professional man to “happen to pass by” the store owned by people whose son was a promising high-school senior in Torah Vodaas. The boy hoped to remain in the Yeshiva, but his parents wanted him to leave for college. Rav Schorr felt that a layman could more effectively influence the parents than a Rosh Yeshiva. The visit was successful, but, because he had promised to remain silent, the emissary told no one of his mission until after Rav Schorr was niftar. Only then did the former student, now a noted Torah educator, learn of the incident.

Rav Schorr was traveling with a professor who had no Yeshiva background but who attended a Daf Yomi session every morning. The professor had not been able to attend his shiur, and was attempting to learn the daf on the train. Rav Schorr asked, “Would you mind if we learned together? I didn’t learn today’s daf yet, either.” Recalling the trip, the professor says, “He surely didn’t need me, but he knew I was struggling, so he gave up his time to teach me a blatt Gemora, and made me feel that I was doing him a favor.”

Students often needed help in arranging suitable matches, finding positions and solving myriad other problems – professional, personal, emotional and financial. He was always ready to help with advice, a telephone call and personal intervention. Many of those who eulogized him were former students who are now at the top of their professions. A common thread in their appreciations, and in the private conversations of hundreds of others, was that he was like a father. One distinguished Rav, who lost his own mother shortly after Rav Schorr’s passing, likened the two in terms of his sense of personal loss.

When the beloved cook of Bais Medrash Elyon, Rav Leib Apfeldorfer, passed away, Rav Schorr was one of those who escorted the niftar to Kennedy Airport to be taken to Eretz Yisrael for burial. Rav Schorr was shocked to learn that the niftar was to remain on a cargo truck unattended until loaded onto the plane by non-Jews. He asked for permission to stay in the truck but was told that El Al security guards ran flashlights across the truck bed when it reached the plane and were authorized to shoot if they came across anyone without clearance. For a suitable consideration, however, the driver would park the truck so that the people with the coffin would not be seen provided they lie flat on the floor. So the elderly Rosh Yeshiva climbed into the truck with three students, and set aside his dignity for the more glorious task of paying a final honor to a man who had served the Yeshiva with loyalty and dedication.

All of these incidents are typical of the man’s mind and heart, as is the fact that they were done quietly or secretly.

He was appointed menahel of Torah Vodaas in 1948 and began functioning as Rosh Yeshiva in 1958, delivering weekly shiurim in Bais Medrash Elyon. Even when he was not formally teaching, however, his greatest satisfaction was as a Rebbe. Throughout his long tenure as menahel and Rosh Yeshiva, he was conscious of the need to broaden the Torah horizons of American Yeshiva students, so he made a point of teaching subjects that were outside of the regular Yeshiva curriculum. In Talmud, for example, he gave late afternoon classes in tractate Mikvaos or in the complex Rav Chanina S’gan HaKohanim (Pesochim 14a–21a), which are invariably omitted from the Yeshiva curriculum.

His greatest impact on American-Torah life, however, came from his horizon-stretching classes and lectures in hashkofa/perspective. He regularly taught Rav Moshe Chaim Luzzatto’s Derech Hashem to Bais Medrash students. Many students attended voluntary classes in Kuzari; often he would return to the Yeshiva for late-night sessions in other limudim (topics), to accommodate the schedules of interested students. For many years, he taught Chumash every morning. Those half-hour classes were classic examples of his mastery of text and commentaries. He would offer major interpretations, spicing them with incisive elucidations and relevant asides. It was not uncommon for him to cite fifteen or twenty sources in a single half-hour class, all important to a clear understanding of the text. The pace was quick and the content tightly reasoned. The manner, like much of his speaking and teaching, had a lightness and ease that belied its penetrating depth. He had a way of choosing the essence of a commentary as it related to textual interpretation, and of categorizing each thought – whether as basic, as a witty aside (a vitz), or as any number of in-between varieties of elucidation.

His regular weekly and pre-holiday shmuessen were dazzling. The reaction of any seasoned scholar who heard him for the first time was invariably one of awe that so much could be compressed into so brief a time: “There is enough content in one shmuess to provide someone else with material for five difficult one-hour lectures.” Scriptural verses, Medrash, Ramban, Maharal, Sfas Emes, Rav Tzodok – commentator after commentator, with one verbatim quote after another, streamed forth.

So casual was his style and so involved was he with the ideas he was developing, that the uninitiated thought he spoke without preparation. No, the preparation was there – not only a lifetime of intense study, but forethought for the particular talk. But as he spoke, new flashes of brilliance came to mind. He would often smile at a new thought, sometimes share the thoughts with his audience, sometimes not – and always punctuate his remarks with a touch of wry humor.

He was a perfect illustration of one of his major themes. He often cited Mabit, Rav Tzodok and others who explain that the reason it was forbidden to commit the Oral Law to writing was because paper cannot capture the vibrant process of a teacher transmitting knowledge through the agency of his personality. The essence of a human being cannot be put on paper; the transcription of his words can never adequately capture the soul that is part of the teaching process. For those who lived through a learning experience with Rav Schorr, the best illustration of the concept is the mere thought of seeing his words on paper robbed of the sight and sound of his unique delivery, the total sincerity of his demand that Bnei Torah not be satisfied with “getting by”, the eloquent expression that the study of Torah is the utmost privilege. To those who had the wisdom to hear him rather than merely sit before him, those memories are an Oral Torah to which no pen can do justice.

He often spoke of zeria (planting). “The deeds of the Patriarchs were like seeds planted in antiquity that bore fruit in their posterity. The Psalmist sings of ‘light implanted for the Tzaddik’, representing the idea that spiritual illumination does not come and disappear like a flash of lightning; it takes root in a suitable host and continuously grows within him, producing ever higher levels of spiritual accomplishment.” Rav Schorr’s students of a generation ago still reap the benefits of ideas and thought-processes that he implanted within them. The spiritual seeds seemed to be esoteric and incomprehensible, even tedious, when first they were presented, but after constant nurturing, they took root imperceptibly and produced rich crops that continue to be replanted and reharvested.

His effectiveness as leader of a Yeshiva seemed to suffer because harshness was foreign to his nature, and students often respond better to the fear of punishment or displeasure than to emotional or intellectual appeal. Nevertheless, his gentle and sincere blend of heart and mind molded students in quiet ways that they frequently recognized only later as adults, when in positions of community or family leadership.

There is a common denominator among them that, upon honest analysis, can be attributed to his influence – scholarship with a breadth as well as a depth, that Sfas Emes-Rav Tzodok approach to Judaism, informality and friendliness, humor aimed at helping rather than hurting, reluctance to accept honors, gentle mocking of the perquisites of position, dedication to Lithuanian lomdus and Chassidic warmth, joy and introspection, a sense of responsibility and generosity.

Many young people face the difficult choice between dedicating their lives to Torah study and education, and turning to more lucrative careers in secular life. As Rosh Yeshiva, Rav Schorr’s opinion was important to many. Typically he would say, “Hashem says, ‘I have separated you from the nations to be Mine’ (Vayikra 20:26), to which Rashi comments that if Jews are separate from the nations, they are Hashem’s people, but if they do not hold themselves unique, they will be prey to Nevuchadnezzar and his ilk. Our essential goal cannot be only to avoid the massacres of Nevuchadnezzar. Rather, it is to fulfill the mission for which we were chosen. The question is not whether the world requires doctors, lawyers, accountants, bricklayers and mechanics. It does. But we were designated to be Hashem’s nation – the nation of the Torah. And each individual Yeshiva student must recognize that it is his privilege as well as his responsibility to live up to his role and be one of those whom Hashem wishes to be His.”

Such was his emphasis. Students should elevate their own sights, not denigrate others. The goal of the Yeshiva was to instill a dedication to Torah study because it made its adherents closer to Hashem, not because it is impossible to be a Torah Jew in the professions or business. He was pained by the polarization that began to cause a rift between those who chose to be exclusively in Hashem’s service, and those who sought to keep a foot in the outside world even while maintaining their primary allegiance to the Bais Medrash. The result of his efforts was imbuing some with heightened aspirations based on a perception of the greatness of Torah, while causing others not to feel alienated despite their choices of careers in other areas.

In the same elevating manner, he urged talmidim to study with all their strength and concentration as well as with all available time. “Learning half the time with full concentration is better than learning all the time with half concentration, because the latter is not truly learning.” And “How can a bochur yawn? Torah study demands interest and enthusiasm; then, there can be no yawning boredom.” He would cite the Talmudic passage interpreting the Scriptural posuk that describes Benoyohu ben Yehoyoda as having killed a lion on a snowy day. The Talmud comments homiletically that Benoyohu studied all of Toras Kohanim in a short, wintry day. Rav Schorr noted the comparison between a man in battle and a scholar taking on a difficult study. “Just as a man fighting a lion, especially in the cold, slippery winter, must give the fray his total concentration, so must a Torah scholar dedicate himself totally in order to emerge victorious in his struggle to master Torah.”

Surely, too, it was no accident that ten years earlier in Bais Medrash Elyon (in Monsey) a group of his students unobtrusively organized an all-year, around-the-clock learning schedule so that people were studying in the Bais Medrash every hour of the day and night. Or that among the significant number who studied all of Thursday night until dawn, some were sure to be at the minyan Friday morning, in response to his insistence that greatness in Torah must never be purchased by the negation of tefilla or other responsibilities.

As the numbers of kollel candidates grew, so grew the financial burdens of Yeshivos. Now that the struggle to gain allegiance to the kollel concept had been won, how could young men be told that their Yeshivos could not provide even the minimal kollel stipend? Rav Schorr began to take increasing personal responsibility for financial matters – first the part of the Bais Medrash Elyon Kollel and then the Yeshiva’s dining room; finally for the Torah Vodaas Kollel in Brooklyn. This voluntary acceptance of obligations was characteristic of the Rebbe who had felt it his duty to buy Pesach suits for his students, and sell his Shas to help Jews trapped in Europe.

In 1952, he dispatched a group of Torah Vodaas students to help found an out-of-town Yeshiva. When the Yeshiva was in a state of financial collapse and could not provide for the personal needs of the students, Rav Schorr took a personal loan of $3,800 for the institution. It took him three years to repay the debt from his own limited salary. Scores of kollel fellows and Yeshiva students received personal checks from him when institutional budgets could not fulfill their obligations. The extent of these private generosities and personal debts incurred to cover institutional responsibilities is unknown. After his passing, however, a drawerful of stale Yeshiva checks was found in his desk; he had covered them for others with his own borrowed funds.

To the public at large, Rav Schorr was the Torah genius and educator; but he played another role that, especially in the last decade, made him one of the most important Torah personalities in the country. He had increasingly become one of those men to whom people turned for guidance and leadership in matters of the utmost gravity. One colleague in AARTS (Association of Advanced Rabbinical and Talmudic Schools) said, “When a new problem arose – one to which we had not yet formulated an approach – he was suggesting solutions when the rest of us had still not fully assimilated all aspects of the problem. His grasp and power of analysis were phenomenal.”

When he was confronted with a responsibility, he would not shirk it. Often he attended meetings when he was ill. Turning aside inquiries about his haggard appearance with a joke, he participated actively while only his closest friends knew that he was not at his best. So much had his presence come to be appreciated at such gatherings, that key meetings were not scheduled unless he was available.

What was unique about him? One major figure in the Torah world, a person who has been at the center of decision-making for decades, put it this way, “He was a Gaon in both Nigle (revealed Torah) and in Nistar (the hidden Torah). What is more, he had a wealth of stories about, and insights into, the great Torah leaders of past generations. He scrutinized a situation through the eyes of Torah and its perspective of history. To say that he was a genius is to tell only part of the story. He was a Torah genius who combined everything that was needed to make life and death decisions.”

It was because of this same all-embracing perspective that he was a conscious, committed Agudist. His mind encompassed Agudas Yisrael as a logical and essential outgrowth of the Jewish past. Agudas Yisrael can be regarded as a necessary vehicle in today’s organized, politicized society, or as a means to make honest and dignified use of availability of public funds, or as a means to rally the community behind the banner of Torah, or as a means to propagate the ideology of Gedolei HaTorah. While it is surely all of these, such considerations are but transitory. Rav Schorr saw Agudas Yisrael as he did everything else, in terms of Yisrael’s historic role. Because he was a Torah genius, he could understand the motives of those Torah geniuses who had conceived Agudas Yisrael at Kattowitz (1912), and brought it to fruition at Vienna (1922). In two presentations at his latest Agudah conventions – once projecting a Torah-view of Agudah, the other time delivering an appreciation of the late Gerrer Rebbe, he painted broad strokes beginning at Sinai and going through the ages. Seen through his eyes, neither Agudas Yisrael nor its leaders represented mere tactics or tacticians. They were worthy of allegiance and sacrifice because they were the bearers of a mission developed by analysis of Scripture, Chazal and commentaries. Because Rav Schorr saw Agudah in those terms, he was a loyal Agudist. The organization had value because it was an expression of Torah’s eternity, so it was his organization.

An examination of his public career reveals one characteristic that was at once a stamp of greatness and its mask. Call it modesty, call it self-effacement, call it disinterest in fame – whatever its name, he displayed a total disregard for the minimal marks of status with apparent indifference to his position on a program or at a dais, the honor accorded him at a wedding or a bris; what did it matter whether or not he received personal credit, as long as Hashem was served, the community benefited, and an individual uplifted. It was thus all too easy to think that because he put his friendly arm around a shoulder and was a friend, that he need be treated merely as a friend. Indeed, such was his wish; but it often resulted in many of us not recognizing his greatness, and as a result we may well have deprived ourselves and our communities of the benefits of his greatness.

It was said of the Chofetz Chaim that his piety was so great that it obscured his scholarship. And it was said of Rav Chaim Brisker that his scholarship was so great that it obscured his piety. Of Rav Schorr we may justly say that his brilliance was so dazzling that it obscured his dedication to study; and his humility was so profound that it obscured his greatness.

Perhaps he wrote his own epitaph. Many years ago, he made the one and only notation he ever wrote in his copy of Sfas Emes. It was on one of the last pieces of Chukas, the Parsha of his passing. All he wrote were the words Haflei Vofeleh – truly amazing with reference to this thought:

Zos HaTorah, Odom ki yomus bo’ohel – the Torah associates dedicated Torah study with purity from the contamination of death. Just as Torah brings purity, so too each Jewish soul is a microcosmic part of Torah, brings life and hence purity, to the otherwise lifeless and impure clod which is the body. Every word and letter of the Torah has within it the capacity to give life to the dead but we do not know how to utilize that capacity.

Rav Schorr’s life gave added purity to a continent. It provided a precedent and set a standard. If we take for granted America’s capacity to produce Torah greatness, if Chassidic youths study Lithuanian lomdus in machshevos haTorah, in good measure it is because the divine plan placed him in America to bequeath it his capacity for life.

Second seder had just come to an end in Torah Vodaas. I had arranged to tutor someone at the other end of Flatbush in less than half an hour. It was a lovely day in Tammuz, and if I started to walk, I would just make it. Then I heard a familiar voice from behind: “Walk me home, Shmuel, and we’ll have a shmuess on the way.” I turned around to face Rav Schorr, who extended to me his usual heart-warming smile. I would walk the Rosh Yeshiva home, and then take a taxi to my destination. It would be worth it.

Why had the Rosh Yeshiva chosen me? In truth, he was friendly to anyone who approached him. I noticed this from the first day that I entered the Yeshiva, five years before. Since then I often took the opportunity to speak with him in Torah and hashkofa. Before long, he extended me an invitation to his home for Shabbos, and it soon became a steady invitation. He was accessible to anyone; one merely had to take the initiative.

And what Shabbosos they were! The Rosh Yeshiva would constantly cite the Gemora: Hashem said, “I have a wonderful gift in My treasure house, and Shabbos is its name” (Shabbos 10b), pointing out that the Shabbos remains in the confines of the Ribbono Shel Olom. The gift is the elevation the Jew experiences to enable him to partake of this celestial Shabbos. Indeed, such was the atmosphere at the Rosh Yeshiva’s home on Shabbos. I’ll never forget the first time I heard him sing his soul-stirring niggun for Kol Mekadesh. With his eyes closed, his concentration and dveikus increased from one moment to the next. With the words Yom Kodosh Hu (it is a sacred day), his intensity peaked, and he repeated them over and over again, as if unable to part with the kedusha of the Shabbos that these words represented.

“Say a Dvar Torah,” the Rebbetzin would implore. “Say something on the Parsha.” The Rosh Yeshiva would lift his head with an expression of genuine humility: “A za shvere Parsha, vus ken ich zogen? – such a difficult portion. What can I say?” He would offer a short Dvar Torah, and then begin another niggun. But many times the Rebbetzin would not be intimidated, and she would insist on more. And then the wellsprings of Torah and chochma (wisdom) would begin to flow. Meshech Chochma, Sfas Emes, Pri Tzaddik, how these seforim would radiate when the Rosh Yeshiva expounded on their contents! And yet most of the conversation was casual in nature. The Rosh Yeshiva was tactfully able to lead a conversation that suited the interests of his guests. And he retained the Shabbos spirit regardless of the topic of conversation.

And then there were the “special Shabbosos”, when Talmidei Chachomim would grace his table. I would witness a remarkable scene: Shas, Rishonim, Poskim and sifrei machshova – all sorts of sources would flow, with the greatest mastery, while the serenity of the Shabbos prevailed throughout.

I recall one Shabbos in particular when the entire conversation of both seudos was saturated with scholarly Torah discussions between the Rosh Yeshiva and one of his guests. Just before bensching the Rosh Yeshiva became pensive, and then he smiled, saying, “I recall a ma’aseh from the Rizhiner:

“Once after Yom Kippur, the Rizhiner announced that he was prepared to tell anyone what that person had prayed for on Yom Kippur, and also how the Bais Din Shel Ma’ala (Heavenly Court) received these prayers. None of the Chassidim had the audacity to test the Rebbe, but one person, not a Chassid, challenged the Rebbe. The Rizhiner closed his eyes, and began, ‘You are a fine Torah scholar, and in your youth you learned with great diligence. Recently, however, family responsibilities have forced you into business, and you’re perturbed that you can no longer afford long stretches of uninterrupted study and prayer. You implored G-d to grant you success in your business so you might once again immerse yourself in Torah and tefilla.

“The man was visibly shaken by the accuracy of the Rizhiner’s statement, and meekly asked, ‘And what was the verdict of the Bais Din Shel Ma’ala?’

“The Rizhiner solemnly continued, ‘The Bais Din Shel Ma’ala declared that although your undisturbed Torah and tefilla was a great accomplishment, Hashem has greater nachas ruach (pleasure) from the effort you exert to learn despite difficulties.’”

The Rosh Yeshiva concluded with tears in his eyes, “Who can say for sure who in Klal Yisrael gives Hashem a greater nachas ruach!”

Our walk together finally came to an end. The Rosh Yeshiva invited me to come in to his home for refreshment, but I excused myself, explaining my commitment. He apologized, “If I had known, I would not have let you walk me.” I assured him that it was my decision and ultimately my gain and I turned to leave. The Rosh Yeshiva then called me again, “Shmuel, wait another moment. I heard an interesting ma’aseh. You know that the Sadegerer Rebbe (fifth generation from the Rizhiner) was recently niftar in Eretz Yisrael. A few days ago, I met someone who was present the night of his passing. He recounted that in the middle of the night the Rebbe awoke and asked for a glass of water. The Rebbe made a Shehakol, lay back down to sleep, and in a few moments returned his neshoma to HaKodosh Boruch Hu. Seforim say that a Tzaddik who lives his entire life with a vibrant emuna that everything that happens is by the word of Hashem, merits that his last words testify to just that: Shehakol nehiye bidvoro – all exists by His word. ”

There was a shadow of envy in the Rosh Yeshiva’s eyes, a longing for that madreiga (level) of living – and passing. The Rosh Yeshiva paused for a moment, then quickly smiled and waved me on.

A few days later, I was standing in the Torah Vodaas Bais Medrash waiting for the hespeidim (eulogies) to begin. I could not believe what had happened. Hundreds of memories rushed through my mind, but my thoughts kept reverting to my last encounter with the Rosh Yeshiva. What had he meant by his last words to me? Then I reminded myself of a story he had once told me:

A talmid of the Rizhiner was with the Rebbe before Sholosh Seudos. The Rizhiner casually asked him, “Can I be yotzeh with peiros (fulfill my obligation – i.e., to eat the third Shabbos meal – with fruits)?”

The talmid quickly cited the Halocha that this was permissible. The Rizhiner remained silent and suddenly the talmid realized that the Rebbe was hinting at his forthcoming passing from the world, whereby his children (peiros) would take his place. “No, Rebbe!” the talmid protested, “The world still needs you!” But it was too late. The Rebbe sighed, “But they are very good peiros.”

Can the talmid be blamed for not realizing immediately the implication of the Rebbe’s words? No. Even had he understood them, would it have made a difference? Hashem counts the days Tzaddikim must stay in this world, and when the time is up, He calls them back to Himself.

(This article originally appeared in the Jewish Observer and is available by ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications ~ Matzav.com)

Divrei Torah of Rav Gedalia Schorr zt"l

By Rabbi Yair Hoffman for 5tjt.com

Rav Gedalia Schorr, was called America’s first Gadol, by Rav Aharon Kotler zt”l. He was a student of Rav Dovid Leibowtz zt”l in Yeshiva Torah VaDaas. When Rav Shlomo Heiman took ill, he asked that Rav Gedlaiha give shiur in his stead. Rav Gedaliah went to learn in Kletzk under Rav Aharon Kotler and later became the Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshiva Torah VaDaas in 1958 after the passing of Rav Reuvain Grozovsky zt”l. He loved and knew every talmid like a father to a son.

The following are eleven thoughts and sayings of his.

The Midrash (BR 8:10) tells us that the Malachim erroneously thought that Adam Harishon was HaKadosh Boruch Hu and wished to say Shira and Kadosh before him. How could this be? The answer is that Adam was created b’tzelem elokim and his neshama is a chailek elokah mimaal. This is our potential!

The concepts of mere resolve and stick-to-it-ism contain tremendous powers of growth. Rav Gedaliah Schorr once said: Yaakov Avinu, even while he was in Galus arose from one madreigah to another. The galus did not affect him negatively at all. His growth was such that the parsha concludes ‘vayifgeu bo malachei hasharais – the angels themselves met with him. The term pagah refers to the notion of chidush – containing an element of shock. The malachim were shocked both of this tremendous growth as well as to the fact that it happened in the house of Lavan. How did it happen? Because he did not deviate one iota from his Avodas Hashem – this resolve was what caused his growth – such growth that even the Malachim himself were in awe. Ohr Gedalyahu Parshas Vayetzai p.98

Part of the Mitzvah of being mesamayach a chosson and kallah is bringing them gifts as the Rambam explains in hilchos Avel 14:1. In the sheva brachos we say about Hashem, mesamayach chosson vekallah. So what is the gift that Hashem brings the chosson and Kallah? It appears that it is the mechilah on all aveiros and the ability to start over – which is the greatest gift of all! (at a sheva brachos)

The entire concept of a Korban being effective to remove aveirah – comes from Avrohom Avinu at the Akeidah. He davened to hashem that in the merit of his willingness to listen to hashem in the Akeida that his descendents houls have the ability to receive mechilah by offering something. From Rav Gedalia’s words we see the kochos of dedication to the ratzon Hashem.

When the Simon Weisenthal Holocaust Museum was opened in California even bringing in stones from Auschwitz to show visitors, he responded emotionally, “They must certainly think that that they are building it so that anti-semites will see how far evil can take them and that they will do teshuvah. The truth is that it will not help at all. These types of places are only school houses of terrorism. It will instruct them as to how far they can strike Jews, may the Merciful One protect us.” Meged Givaos Olam Vol. II

That which they say “the Shabbos after Shavuos” we still retain the sparks and light of Yom Tov – that Shabbos [when combined with its kedusha and that of the sparks and lights from Shavuos] is a very special time for hisorerus. The Maharsham had a proof to this from a teshuvah of the Radbaz Vol. Vi #2178. The Gemorah in Chagigah 26b states that after [every] yom tov the Kohanim would show the people the nissim that the lechem hapanim would still be fresh and warm and how much Hashem loved Klal Yisroel. This happened on Shabbos. Now why were the people there Shavuos? It was because they stayed. This si why it is called Shabbos noch Shavuos – and it has special Kedusha.

The Midrash Bereishis Rabbah 60:2 tells us Eved maskil – zeh eliezer. Now each person has a particular mission or task in life – whether he admits to it or not. He must fulfill this task to his best ability. He should not try to rid himself of that task. What was the wisdom of Eliezer? The main aspect of his wisdom is that he knew his task and place. His place was the be the servant of Avrohom and through that he can achieve the apogee of what he was meant to do. He did not try to releive himself of this task or his responsibilities. This must be true of all people. We must recognize our task, and the particular strengths that shamayim has given us. We must serve Hashem with these kochos and not search for other aspects and heights that were not meant for us. Eliezer performed his task with all his abilities.

Rav Menachem Zeimba zt”l wrote remarkable chiddushim on the entire Torah. The gzeirah that was the Churban was not only on him – but also on his Torah chiddushim – which could have enlightened all of Klal Yisroel. Only two seforim were saved: Totzaos Chaim and responsa Zera Avrohom. It is remarkable that these two seforim were printed as a chessed – to commemorate the memory of two Talmidei Chachomim. This was Torah of chessed – and that is why his Torah was saved from the Churban.

When someone does an action – there are not only different levels of intent, but different types of intent as well. Rav Schorr zt”l would quote Rashi (Bereishis 9:23) on the pasuk of how it says, “And he took, Shaim and Yafes, the clothing and draped it on Noach. WRashi explains that Shaim exerted himself more in the Mitzvah than Yafes did. He therefore received the Mitzvah of Tzitzis for his decendents, while Yafes merited burial for his descendents as it says in Sfer Yechezkel 39:11 And I shall give Gog a burial place. Now the action that they each did was the same. The difference between them pertains to the type of intent that they each had. Shaim’s intent reflected inner depth, true understanding and for the sake of a Mitzvah. This is why he merited to a Mitzvah that reflects the inner nature of clothing. Yafe’s intent was external and aesthetic – so that things should look nice. This is the essence of Yavan to focus only on the out aesthetics and ignoring the inner depth and value.

And Mordechai knew all that had transpired (Esther 4:1). Rashi explains that he was told this information in a But how does Rashi know this? How do we know that it wasn’t through Ruach haKodesh or through Eliyahu HaNavi – as is indicated in the Midrash (Esther Rabbah)? Rav Schorr explained based on the Gemorah in Chagigah 5b, “And I shall surely hide My Face on that day” – Even though I shall hide My Face from them – I shall speak to him in a dream (BaMidbar 12:6). Even in a period of Hester Panim – Klal Yisroel will still merit communication through a dream.

There are two types of yirah. There is one that is calculated and developed intellectually. But there is a more fundamental yirah – one that exists naturally, like that which is found in the Beis HaMikdash as in the tefillah vesham naavadcha b’yirah. The main yirah is when there is a divine revelation and based upon the understanding of the person he is filled with true Yirah. (Ohr Gedalyahu parshas beshalach)

The author can be reached at yairhoffman2@gmail.com