Rav Yoel Teitelbaum zt"l

הרב יואל בן חנניה יום טוב טייטלבוים זצ"ל

Av 26 , 5739

Rav Yoel Teitelbaum zt"l

Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum began his rabbinic career in Krooly, a small town in Hungary. In 1929, the Rav of the Orthodox community in Satmar, a larger and more prestigious community, passed away, and Rabbi Teitelbaum was invited for a Shabbos “tryout.” The Rav displayed exceptional knowledge of Talmud, far above the prevailing image of a Chassidic rabbi, who was expected to be more of an expert in Kabbalah and prayer. He was retained by the community, which prospered under his leadership, and began attracting students to its yeshiva from all over Hungary.

As the War approached, the Satmarer Rav was smuggled out of harm’s way, first into Switzerland, where he remained throughout the War, and afterwards in 1946, into Israel. On a fund-raising mission to the United States, he met many people from his former community who urged him to stay in America and help them recover from the trauma of the War. Rabbi Teitelbaum’s decision to stay in America was historic, in that it set in place the foundation for the growth of the Satmar community. After only a short time, the transplanted “Yetiv Lev” Congregation emerged upon American soil, with Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum at the helm.

In 1948, he drew worldwide attention when he became the only Jewish leader to denounce the newly founded Jewish state. He based his Anti-Zionist position on a gemara in Ketubot 111a, that derives from the triple mention in Shir HaShirim of the verse, “I have bound you in oath, O daughters of Jerusalem,” that Hashem bound the Jewish People and the nations of the world with three oaths:

1. “shelo yaalu bachoma” – that the Jews should not forcibly “breach the wall,” and enter Eretz Yisrael

2. that the Jews should not rebel against the nations of the world

3. that the nations of the world should not oppress the Jewish People excessively during the Exile

The gemara concludes with the threat that if the Jews would violate these oaths, Hashem would bring upon them great harm and physical destruction. Rabbi Teitelbaum claimed that the Zionist movement had brought the Holocaust upon the Jewish People by violating the oaths incumbent upon them.

(Two of the arguments raised against the above are that by the Balfour Declaration the nations of the world gave permission to the Jews to return to Israel. Another is that the oaths would apply to the Jewish People only if the nations of the world did not excessively mistreat them during the Galut. Centuries of massacre and pogrom certainly testify otherwise as to the behavior of the nations of the world. If the nations have violated their oath, the oaths upon the Jewish People are null and void.)

In the 1950’s, the Satmar community continued to blossom. Williamsburg became the scene of many inspiring Chassidic gatherings and public tefilos, such as would occur annually on Hoshanah Rabbah, when the Satmar synagogue was a sea of lulavim and esrogim.

By the 1960’s, the Satmar community in Brooklyn had grown rapidly and the rebbe had gained many new adherents from immigration to the United States, and his opinions and blessings were sought by thousands.

In the 1970’s, the rebbe bought land in Monroe, NY, and founded Kiryas Yoel, where a large branch of the Satmar community now lives.

Tens of thousands of his Hasidim attended his funeral in Kiryat Yoel. None of his children survived him, as all three of his daughters passed away during his lifetime. The Satmar community grieved at the tremendous loss of their rebbe, who had led his followers according to uncompromising principles, in which he deeply believed.

Remembrances of a talmid, as told to Rabbi Nisson Wolpin

The Satmar Rav, a direct descendant of both the famed Yismach Moshe and the Chavas Daas, was recognized as a young man for his unusual lomdus, hasmadah and tzidkus – Torah scholarship, diligence and piety – assuming his first rabbinical position as Rav of Muzheyer at the age of seventeen. By the outbreak of World War 2, he was Rav of the thriving community of Satmar and had emerged as one of the leading figures in Hungarian Jewry. He distinguished himself with his heroic adherence to Torah under the most brutal conditions of the Nazi concentration camps. After a brief stay in Eretz Yisrael, the Rebbe came to America in 1946 and settled in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn.

It was in Williamsburg that the Rebbe painstakingly helped thousands of fellow survivors reconstruct their lives, at the same time reconstructing a thriving Chassidic community – taking advantage of all technological advances of contemporary America, while shunning its values and the more apparent aspects of its life-style. As a result, at the time of his passing, the Rebbe presided over a tight-knit, highly disciplined community numbering in the thousands, with major settlements in Williamsburg and elsewhere, including their flourishing Kiryas Yoel in New York’s Monroe Township, Monsey, Montreal, and of course, Jerusalem, where he was Rav of the Eida Hachreidis.

Indeed, the Satmar communities are all distinguished by a kehillah system that include complete control of shul, kashrus, education, and in many cases, social welfare. Thus, the Brooklyn kehillah embraces an educational system of 5,000 students embodying a complete girl’s school and yeshivos spanning nursery through Kolel, as well as an extremely effective tzeddakah-medical-welfare system and wide-reaching Bikur Cholim network, directed by the Satmar Rebbetzin. This, in a smaller format, is duplicated in the rolling expanses of Kiryas Yoel – the Satmar sponsored suburban settlement.

The Rebbe was renowned for his extremely strong stand against Zionism, even refusing to accept the existence of the State of Israel – differing markedly with Torah authorities of Agudas Yisroel in this. For that matter, he opposed the very concept of an organized coalition-structured Orthodoxy as personified by Agudas Yisroel. Nonetheless, he was respected – even revered – in other circles for his vast scholarship, tzidkus, personal humility, astute wisdom, and unwavering tenacity.

The 100,000 people that crowded the streets of Monroe to bid farewell to the Satmar Rav included followers and admirers, Chassidim and Misnagdim, Europeans and Americans, paying homage to one of the greatest of contemporary Jewish leaders, who had taught and led his people as a Rav for seventy-five years … He will be missed – not only by those who followed his particular ideology, but by Orthodox Jews of contrasting viewpoint as well who saw in him a tower of principled leadership.

Of the hushed tens of thousands that came to pay their last respects to the Satmar Rav at his funeral, a large number were members of other communities – various Chassidic groups, yeshiva circles, and out-and-out Misnagdim. They came out of deference to a giant of vast scholarship, who had symbolized a rare level of personal devotion to G-d as well as a demanding, inspiring leadership of a type that has largely disappeared from the world scene. As Rabbi Yitzchok Hutner (Rosh Yeshiva of Mesivta Rabbi Chaim Berlin – Gur Arye) had said regarding the Satmar Rav on an earlier occasion:

Noach suffered a maimed leg as punishment for the one time that he was late with the lion’s meal in the Ark. It would seem that Noach should have been forgiven this one tardiness. But a lion is king of the beasts, and is worthy of service in a manner that is in keeping with its royal position, without any exceptions – especially this particular lion, which was the last of its kind … The same, said the Rosh Yeshiva, may be said of the Satmar Rav. “I’m here to honor him because he’s the last of the lions.”

A great many of those present at his funeral were paying tribute to “the last lion” – the last leader of his kind in our midst.

The Purity of Another Era

They had heard of the Sigheter Rav’s “wonder sons” who were only little children, ninety long years ago. It was said that “Yoilish,” the younger child, refrained from unnecessarily touching covered parts of his body, so he could always be prepared to study Torah. A visiting Rabbi asked the Sigheter Rav if it were so. “Come,” said the Rav, leading the visitor to the bedroom where his three-year-old Yoel was fast asleep. He lifted his tzitzis-fringes over the child’s head and tickled his ear. The sleeping boy slipped his sleeve over his fingers and raised his covered hand to scratch his itchy head.

From the time of his Bar Mitzvah until the outbreak of World War 2 – a period of forty years – Reb Yoel never slept on a bed, except for Shabbosos – studying Torah, on his feet, by day and by night … In the internment camp in Bergen-Belsen, not only did he eat nothing that might have been un-kosher, subsisting mostly on potatoes, but he fasted as often as four times a week.

He continued this procedure until his last days; and even when he did eat, his first meal usually was a cup of coffee at 3 or 4 in the afternoon … “Do I want to eat now? A Jew doesn’t eat because he wants to. He eats because he must.”

While he encouraged his followers to work and earn well, spend on themselves as necessary and give charity lavishly, he avoided spending on himself. Any time he was presented with a new garment, his first reaction was: “Who needs it?”

The Rebbe was fastidious about his personal cleanliness, and would not tolerate a hint of uncleanliness. In part, this was to be fit for prayer and Torah study. In fact, he thought nothing of changing clothes several times during the day if he found them unclean. Even in Bergen-Belsen, he had bartered food for tissues …

Unknown to many, he was also meticulous about precision in time and manner of performance of mitzvos. Only his Shacharis was invariably late because of his personal preparations … On occasion, he could not begin his Pesach Seder until after 11 o’clock because of ill health. This did not deter him from eating the afikomen before midnight, as is required by halachah, according to many … He also consulted an authority present at his Pesach Seder regarding the precise size of his matzos and marror, as is required by halacha for the mitzvos …

He took pains to shield his knowledge of Kabbalah from the curious. The Rebbe was always surrounded by people – indeed, he enjoyed company; but he was sensitive to prying eyes. He made light of references to mofsim (miracles) or kabbalistic involvement in our times. Yet his conduct at meals – the ways he picked at his food, and his deep concentration in tefillah, bespoke hidden motives, meaning-laden cryptic gestures.

While he made himself available to people without hesitation, and seemed to enjoy conversing with all his visitors, the Rebbe had a distinctly regal bearing. When walking down Bedford Avenue from his home to the bais hamidrash, the sidewalk would clear well in advance of his coming. Not that there was anything forbidding about his appearance. But, until his very last years, a vitality seemed to shine through his smooth, translucent face that bespoke a purity that defied the passage of time, and inspired others to move back in awe.

The Vast Sea of His Knowledge

It seemed as though he never had to prepare for a lecture, drashah, or shiur. In Europe the custom had been for someone to open a Midrash Rabba at Shalosh Seudos, and read three passages at random – giving the Rebbe material for his dissertation. He would then expound at length, quoting passages from the Midrash verbatim … In America, he would enter the yeshiva’s bais hamidrash, ask where the bachurim were up to in their studies, open the Gemara and begin a long, involved lecture without further notice.

Rabbi Yaakov Breish of Zurich had spent years on the section of his sefer Chelkas Yaakov that deals with the complicated laws of ribbis (usury). When visiting the United States, he visited the Satmar Rav and spent several hours discussing in detail several difficult topics in his sefer. He later expressed wonder at how thorough the Rebbe’s mastery of this topic had been, even though his visit had been unannounced, giving the Rebbe no time for preparation.

The Rebbe would write his Torah commentaries at two or three o’clock in the morning, relishing every minute. He once remarked, “I could see myself doing this the rest of my life, but I have a directive from my father that one must be prepared to give away his own Torah, if necessary, to help a fellow Jew.”

Notwithstanding his round-the-clock involvement in chessed, his treasure house of Torah knowledge was vast. Perhaps Klal Yisrael was deprived of the greater riches that would have been theirs had he been allowed the luxury of extending the full measure of the hasmadah of his youth into his later years, and not suffered the distraction of being father to his community. But then, Klal Yisroel would not have had a Satmar Rav, and we would have been infinitely poorer for that loss.

Father to His Community

A large number of those at his funeral had come as children mourning a very personal loss, many of them ripping their garments in kriyah for the loss of a father who had cared for their every need, both spiritual and material. It is extremely difficult to comprehend how so many thousands could experience such an intense relationship with one man. And yet, how else can one explain the phenomenal growth of the Satmar community from several scores of families in the late 40’s to so many thousands of followers today – especially when the external trappings of the group’s lifestyle is in direct conflict with modern Western culture? To be sure, the explanation for this growth lies in part in the large families generally prevalent in the Torah community. But it also must be attributed to the exceedingly low defection rate among Satmar Chassidim – a phenomenon in which the Rebbe played a pivotal role.

Shortly after he had arrived in America, a young Chassid was discussing the naming of his newly born son with the Satmar Rav, in the presence of another rabbi. “My grandfather was a very good Jew,” he said.

“His name would be a fine choice for your son,” commented the Rebbe.

“But several of my nephews and cousins already carry his name. On the other hand, my father-in-law has no one named after him.”

“That should certainly be taken into consideration.”

“However …”

And so it continued. After the young father left, the other visitor asked the Rebbe why he permitted himself to become so involved with trivia.

“In the old country, I was a father at home, and could be a Rebbe in the city. But here,” the Rebbe sighed, “this is simply not suitable. I have to be a father to my community, and a Rebbe at home.”

As visitors streamed into his room, the Rebbe asked questions and listened carefully, seemed to bend his shoulder to carry the load of others, and was mispallel (prayed) for their needs.

His manner of closely examining a kvittel, looking for clues – and, amazingly, “discovering” errors in the writing of the name of a total stranger (“You write ‘Binyamin ben Leah’ – isn’t there more to the mother’s name? – You say ‘ben Leah Esther’? You should have written it so!”) – and the encouraging word he invariably offered, comforting the petitioner… Stories are legion about occasions when – after hearing the details of a person’s problems – the Rebbe swept his table clean of the day’s accumulation of pidyon gelt (monies for charity, given to the Rebbe by people petitioning for his help and prayers) to give to a needy visitor . . . Nor did he limit his compassion and sharing of joys and sorrows to his own immediate group:

The Latin American lady not at all dressed in Satmar tradition, who needed money for her son’s hospitalization and left with the full amount… The man who wept bitterly for all his suffering, and walked out with the entire day’s proceeds. Then the Rebbe was informed that the man was a fraud. “Baruch Hashem!” exclaimed the Rebbe, “I’m so relieved that he’s not in such terrible straits!”… The editor of an Israeli journal that had slandered – even ridiculed – the Rebbe, was in his room, sobbing for his daughter’s terrible personal plight – she was engaged to be married but lacked sufficient funds to purchase an apartment. After the Rebbe had given him a large sum of money, someone whispered into his ear, “Don’t you know who that was?” “Of course I do,” replied the Rebbe, and then – after a moment’s hesitation – called back the editor and gave him even more …

An alumnus of a Lithuanian-type yeshiva in Israel sat near the Rebbe at his Pesach Seder. The Rebbe was amused at his guest’s pompous measuring of the precise portion of food and drinks required for the rituals (even though the Rebbe himself was no less fastidious). As the guest prepared his matzos, the Rebbe asked him, “Are you sure it’s the right shiyur (required amount)?” Similarly, after he ate the marror, and later when he eyed his afikomen before consuming it, the Rebbe smilingly asked, “Is it the shiyur?”

Finally, the fellow put down his matzah and said, “Rebbe I’m not sure. But isn’t it the shiyur of tcheppen (teasing)?”

The Rebbe was deeply disturbed that he had actually offended the man with remarks that he had only meant as a friendly exchange. He begged his forgiveness again and again, as was his habit when he felt he had mistreated someone. Finally he asked him, “Please see me right after Yom Tov.”

When the man reported to the Rebbe, he asked, “Why are you here? Why did you come to America?”

“I’m here because I must raise five to six thousand dollars to marry off my daughter.”

“I’ll get the money for you. And please – any children that you will be marrying off in the future – come here and I’ll take care of your financial needs.”

The Satmar Rav was not satisfied until he had financed the weddings of the man’s four daughters.

Builder of a Community

While the Rebbe’s personal warm concern for each individual was surely a key factor in the unusually low drop-out rate among his kehillah’s members, there are additional factors in his leadership that also account for this phenomenon.

When he settled in Williamsburg shortly after arriving in the United States, he found a handful of his followers in a bais hamidrash all day, saying Tehillim, learning Chok – and spending their time in “the Rebbe’s Court”. He summoned them to him and insisted that they find jobs to support their families. “If I had the strength (he was in his sixties at the time) I’d also go to work.” … He felt that he could not be oblivious to the stress on material well-being that marks American society. Here, especially, one had to be mindful of the dictum: “Poverty can sway a man from loyalty to his Creator.” Moreover, a viable community could only take shape if it is self-supporting on a level comparable to that of the surrounding society. By the same token, he guided his followers to give tzeddakah expansively – not to shy away from a sweeping gesture of generosity. Today, members of the Satmar community are active in all phases of business and commerce, as well as in a wide spectrum of occupations, ranging from grocers to computer programmers. And the community itself supports a host of social services, most notably its bikur-cholim program – administering to the sick, with fleets of cars and vans carrying hundreds of volunteers to hospitals all over New York, throughout the day.

A Klal-Yisrael Curriculum

The Rebbe founded the Yeshiva Yetev Lev and the Bais Rochel School for girls, both adhering to the syllabus of pre-World War 2 Satmar. The Yeshiva emphasizes a rapid pace of study, familiarity with a broad range of topics, and an eye on practical application, through halachah. The girls’ school follows a strictly prescribed Hebrew curriculum. Yet the Rebbe was keenly aware of the surrounding yeshiva scene. In fact, shortly after his arrival in the States he delivered shiurim in the bais hamidrash of both Mesivta Torah Vodaath in Brooklyn and the Telshe Yeshiva in Cleveland, in response to invitations from the yeshivos’ respective leaders.

On a visit to Bais Medrash Elyon in Monsey, the mashgiach, Rabbi Yisroel Chaim Kaplan, who took great pride in his Kollel, asked the Rebbe why his kehillah does not include one. He replied, “You are raising an elite of gedolei Yisrael. I hope to establish a broad Klal Yisroel. I dare not sacrifice the average students for the sake of the isolated individual of rare promise.”

Nonetheless, the Satmar Rav did recognize the necessity of grooming a leadership of expert talmidei chachamim, and from the modest beginnings of several young men studying privately in his home, he eventually founded a full-fledged kollel, with emphasis on psak halachah.

Before the kollel’s formal opening, it was announced that the Rebbe himself would screen prospective members – but not until after their wedding. The first candidate came in, nervously anticipating a grueling test on Talmud and commentaries … “How many people did you invite to your wedding?” asked the Rebbe. “At how much per couple? … What did your furniture cost? … So much? And you want the community to support you? Forget about it. Kollel is not for you.”

As exacting as he was in choosing kollel members, he was forgiving in dealing with his yeshiva students, never expelling a boy from his schools – for how does one expel someone from the Jewish community?

The Festivals in Satmar

The Satmar sense of community was especially apparent when the Yomim Noraim Season began – first Selichos, with the Rebbe leading with his frail voice, precise in nusach, heart-rending in emotion . . . his pouring forth of soul on Rosh Hashana, and then on Yom Kippur, crowned by his Ne’ilah … Then Hoshana Rabbah, when thousands – literally thousands – would crowd the Satmar bais hamidrash to be with the Rebbe, with hundreds of “outsiders” who joined the mispallelim to watch as the Rebbe sang the Hallel, and waved his lulav, cuing thousands to follow his lead – southward, northward, eastward, up, down, westward – “Hodu – let us praise G-d” – “Anna Hashem – Please G-d, help us, save us!” Waving to and fro, as if the Rebbe were himself waving a thousand lulavim – not lulavim, but waving a thousand souls in praise and supplication … Watching as he led his Chassidim in the Hoshanos, weeping, and pleading with them to strive for personal improvement, for sanctity – urging them in his moving address, to join him in calling to G-d to “Help us lema’ancho – for Your Sake!” … Then Simchas Torah, when the sea of humanity compressed into his bais hamidrash would split, opening a path for the Rebbe, carrying his diminutive Sefer Torah; voices rising and falling in song like breakers on a shore; his tallis draped over his head, shielding his eyes, swaying for a moment, and then running – or dancing – or floating – it’s difficult to say which . . . somehow he seemed to be borne aloft by the swell of voices. How else could he stay on his frail, suffering feet for six hours on end?

And then, after Yom Tov, the triumphant torchlit march accompanying the Rebbe home, closing the season.

One Man Alone

The patriarch Avraham was also known as “Avraham HaIvri,” because he came to Canaan from Eiver LaNohor, the other side of the river. This title has also been explained to refer to his position as one man against the world – “Avraham be’eiver echad – one man alone on his side,” believing in monotheism, while the entire world was on the other side of the issue.

This one trait assumed major significance: When any of Avraham’s contemporaries was asked about his beliefs, he would reply, “Of course, I am an idol-worshiper.” Then, even though he well could have ignored monotheism, since Avraham was its only exponent, and idolatry was the universally accepted belief of millions, he would add: “There is another approach: the monotheism of Avraham. ”

That Avraham could single-handedly invade the consciousness of the entire world and create in their minds the possibility of ”another approach” was most noteworthy. Thus, it was perpetuated in his name – “Avraham Halvri.”

The same may be said about the Satmar Rav. Most of world Jewry had accepted the Zionist dream. And even many among those who had rejected its limited, secular definition of Jewishness were excited by the emergence of the State of Israel, and the miraculous victories in ’48, ’56 and ’67. The Satmar Rav was often alone in consistently condemning the State as the pure embodiment of a secular ideal, a ma’ase Sattan: dismissing victories on the battlefield as an ideological minefield; opposing mass aliyah as a violation of the Three Vows (T.B. Kesubos 11a : Binding Jewry not to force its way into Eretz Yisrael, nor to rebel against the nations, and the nations not to subjugate the Jews excessively.) for settling the country in defiance of world opinion; and participation in the government in any form – even voting in national elections – as strengthening a reprehensible concept by implied recognition. Like some other schools, those of the Eida Hachreidis, which is in the Satmar orbit, do not accept funding from the Israeli government.

Advisors had begged the Rebbe to omit from his writings his directives against going to the Kosel, as being too difficult to accept, sure to result in the alienation of many of his followers. He commented, “I don’t care if I’m left with only one minyan of adherents. I’ll not refrain from expressing my beliefs.”

He was once advised by a close associate, “Don’t let yourself get so upset!” The Rebbe replied, “There are a thousand reasons not to reveal the Emes, If one gets upset, he can forget himself for a moment, and then at least a bit of Emes comes through.”

The mainstream of the Torah leadership did not subscribe to his approach toward dealing with the Israeli government. Even those most strongly opposed to the State’s philosophy accepted its existence and, at worst, felt compelled to deal with it as they would with any government that ruled a land where Jews lived. At times they were deeply upset with his unyielding approach – such as Rabbi Aharon Kotler’s vexation with the Rebbe for “publicly opposing the Chazon Ish, Reb Isser Zalman Meltzer, the Belzer Rebbe and the Tchebiner Rav – all of whom held that voting in Israeli national elections was an obligation on every Torah Jew who took the needs of the Yishuv to heart.” Nonetheless, they were always aware of the Satmar position and often measured their stance against the extremes of the Satmar-Neturei Karta ideology. And even the most rabid, anti-religious secularist was aware of the “on the other hand,” represented by this one man’s uncompromising stance.

His ideology is represented by his two seforim VaYoel Moshe and Al Hage’ulah V’al Hatemurah, written with vast scholarship and great care – as well as by his spoken word on numerous occasions.

In spite of the difference between them, a current of admiration flowed between the Satmar Rav and the heads of American Yeshivos. Said Reb Aharon Kotler: “The Satmar Rav and I do not have the same approach – neither in Torah study nor in political matters – but I must say, he is a giant in Torah and a giant in midos.” The Satmar Rav, in turn, spoke at Reb Aharon’s funeral, weeping, quoting Rashi (in Be’haaloscha): “‘The praise of Aharon is that he did not deviate’ – Reb Aharon remained ever faithful to his tradition, never deviating.”

Similarly, Rabbi Reuvain Grozovsky, the late Rosh Yeshiva of Mesivta Torah Vodaath and Bais Medrash Elyon, who had headed the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah (Council of Torah Sages) of Agudath Israel, had made it a policy of never responding to criticisms “from the right” because its adherents are G-d-fearing Jews, and there may well be some elements of truth in their approach (Beiyos Hazman pp. 69-71)…. Indeed, Reb Reuvain had often cited a statement by his father-in-law, Rabbi Boruch Ber Lebowitz, a leading Rosh Yeshiva in pre World-War II Europe: “The Satmar Rav was the person to contact whenever the Polish and Lithuanian leadership had need to communicate with Hungarian Jewry.” When the Satmar Rav visited Reb Reuvain when he was ill from the stroke that had partially paralyzed him, the Rebbe wished the Rosh Yeshiva: “A refuah sheleimah – a complete recovery, so we can battle each other once again.” … Several years later, when he returned home from Reb Reuvain’s funeral, the Rebbe seemed unusally depressed. To his Rebbetzin’s question as to why he was so troubled, he replied, “The world has lost an lsh Ha’emes – a man of rare integrity.”

It was not only in regard to its extreme anti-Zionism that the Satmar Rav had molded his community as “a group apart,” in the manner of Avraham Halvri. He also guided it to being distinguished in its total lack of compromise in mode of dress – not yielding to American pressures, neither in style nor in lack of modesty. If anything, the newer generations have reinforced their dedication to the standards of “Jewishness in dress” that had prevailed in Satmar of old making it much easier, one might add, for the American yeshiva community to adhere to its own standards of propriety without developing a sense of being at the outer edge of society.

Thus, the Satmar Rav’s relentless demands for the highest religious standards proved to be an important contribution toward changing the complexion of a significant segment of Orthodox life in America. Witness: Holocaust survivors and their American-born grandchildren – dayanim (rabbinical judges), rabbanim, diamond polishers, computer technicians, and gas-pump attendants among them – who proudly walk the streets of the New World in traditional garb, making the shtreimel an everyweek feature of many communities.

For evidence of the living legacy of the late Satmar Rav, we tend to look at the self-contained communities of his followers that crowd this or that old-world corner of various urban centers; or that are found in unlikely suburban locations, such as New York’s Monroe township or Rockland County. But, in many respects, his influence has extended beyond the confines of his immediate following, for those whose compass is set by other stars cannot help but have had their own awareness sharpened by the perspectives of the Satmar Rav.

After all, who can live in the same community as a tzaddik – or even in his time – and not be affected by his presence?

When Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetzky spoke at the unveiling of the matzeivah (monument) at the gravesite of the Satmar Rav, one week after his passing, he commented on the special gift G-d had bequeathed on our generation through the presence of the Satmar Rav for over nine decades:

“When an era closes, there is always a danger that the succeeding generations will be oblivious to the values and special character of their predecessors. Thus G-d often grants one exemplary member of the preceding era longevity, to permit him to teach the next generation how the old generation lived – by his mere presence. Thus did Rabbi Yehudah Hanassi – who closed the era of the Tannaim by writing the Mishnah – continue to ‘frequent his home’ for decades after his passing; and Rabbi Yochanan, who compiled the Jerusalem Talmud, lived for hundreds of years…; and thus did the Satmar Rav grace our generation with a greatness in scholarship and piety that had been identified with the glory of days gone by.”

{This article originally appeared in The Jewish Observer and is also available in book form in the ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications Judaiscope Series.}

{Matzav.com Newscenter}

Stories of Rav Yoel Teitelbaum zt"l

One Motza’ei Shabbos Kodesh, parshas Eikev, the Tosher Rebbe sat at Melave Malka with his Chassidim and related:

This upcoming twenty-sixth of Av is the Yahrzeit of the holy Satmar Rav. Even before he was born, the Sanzer Rav, author of Divrei Chaim, testified as to his upcoming greatness. Rav Yoel’s father, the author of Kedushas Yom Tov, was childless for many years and when he came before his Rebbe, the Sanzer Rav, the Divrei Chaim promised him in a letter that he would have children blessed by Hashem. His prophetic words were, of course, fulfilled: the Kedushas Yom Tov had two luminaries, his sons Rav Yoel of Satmar and Rav Yoel’s brother, the holy author of the Atzei Chaim of Sighet, as well as several daughters. From the sanctity and righteousness of these two brothers alone, we see that the Sanzer Rav’s blessings were fulfilled and that the Kedushas Yom Tov merited children blessed by Hashem. The Kedushas Yom Tov’s grandfather, the Yetev Lev of Sighet, was similarly blessed at his wedding by Rav Tzvi Hirsch of Rymanow that he, too, would merit children, generations blessed by Hashem. Obviously the Satmar Rav was one of the blessed descendants of this beracha.

(The Tosher Rebbe Shlit’a related the story of the Yetev Lev’s chassuna in greater detail on Motza’ei Shabbos Parshas Toldos in the context of Rav Hirschel of Rymanow’s Yahrzeit.)

Rav Hirsch of Rymanow was a Kohen and had the minhag to bless Klal Yisrael, bestowing abundant berachos and goodness upon them. Whatever he said was fulfilled. When he was younger, before he became well-known, he still had great power to dispense berachos, as I heard from my grandfather about the chassuna of the Yetev Lev of Sighet and this is the story he told me (here the Tosher Rebbe Shlit’a retold the story heard from his grandfather):

When the Yetev Lev married the daughter of Rav Moshe Dovid Ashkenazi, the Av Beis Din of Taltsheva, the grandfather, the author of Yismach Moshe, gave his son Rav Elazar Nissan (the father of the chosson) a certain amount of money to distribute as tzedaka to the poor who were present at the chassuna. Amongst the poor there was one particular pauper who, having received the allotted amount of tzedaka which Rav Elazar Nisan distributed to each one, insisted that he add more money to the amount and asked for a certain very large sum - so large that Rav Elazar Nissan kindly told him that the money was not his and he could not use his discretion to give one pauper such a princely sum.

He turned and went to his father, the Yismach Moshe, related the pauper’s request and asked him what to do.

“I wish to see this pauper,” said the Yismach Moshe, and from his room the crowd parted so as to allow him to peer through the door and see the face of the anonymous pauper who had requested such a sum of tzedaka. When the Yismach Moshe saw who it was, he turned to his son, Rav Elazar Nissan, and told him to give the poor man the entire sum of tzedaka he had requested, without arguing.

When the pauper received the money, he blessed Rav Elazar Nissan and the Chosson, the Yetev Lev, with a great beracha, promising them that from this marriage would come forth generations of holy righteous descendants. Afterward, he vanished without a trace.

Many years later, when the Kallah’s father, the Taltsheca Rav, prepared to move to Eretz Yisrael, his son-in-law, the Yetev Lev, accompanied him to visit many Rebbes and Tzaddikim, among them Rav Hirsch Rymanower. The Yetev Lev immediately recognized his face – it waste pauper who had attended his wedding so many years before, who had blessed him with descendants who would be Tzaddikim. Among those descendants was the Satmar Rav.

When the Satmar Rav was a six-year-old lad, he merited to visit the holy sanctuary of Rav Mordechai’leh of Nadworna. Rav Mordechai’leh asked the young child what he was studying in cheder. Rav Yoel answered that he studied Chumash with Rashi’s commentary. Rav Mordechai’leh farhered (tested) him and was pleased to see he knew the material well. He then told him to be very diligent in studying Chumash with Rashi every week, saying, “Mordechai’leh knew several great men, who, in their older years, they did not know where HaKodosh Boruch Hu dwells, because they were not diligent in studying Chumash with Rashi.” He promised the young Rav Yoel that if he would diligently study Chumash Rashi week by week, he would rise to very high levels.

The holy Satmar Rav fulfilled these words all his life. The words of Rav Mordechai’leh were very precious to him: every day after davening, while still adorned in tallis and tefillin, the Satmar Rav studied Chumash and Rashi; even in his old age when this practice was difficult and taxing for him, he never gave it up.

The Satmar Rav’s kochos in Tzedaka were very great. He would give out huge sums to the poor and destitute, looking after their needs and helping to care for them.

When he was Rav in Kruly in his younger years, the Satmar Rav asked his gabbai to invite the wealthy Rav Chaim Shtern of Pest and explain that he had an urgent and important matter of business to discuss with him. When Rav Shtern arrived in Kruly, Rav Yoel explained the reason for his summons: “You should know that in Pest, there are approximately forty families I know of who are so destitute that they cannot even put bread on their tables. I am asking you to please see to it that at least their needs for Shabbos are taken care of.”

Rav Chaim answered Rav Yoel, “Surely I will fulfill what the Rav is asking of me, on one condition – that the Rav does not make me a Chassid!”

Rav Yoel smiled and answered sweetly, “Mein tei’ere kind (My precious child)! Why, if you fulfill my request and take care of fulfilling the needs of the poor, I will be your Chassid!”

(Based on Avodas Avodah Sichos Kodesh II)

Once, after the war, a young man approached the Satmar Rav for a beracha. “What makes you think I can give you a beracha?” asked the Tzaddik.

"Someone whose opinion counts even in heaven surely has the right to bestow berachos," answered the young man.

"Well, if you could prove that were true about me, surely I would bestow my beracha upon you. Any person who knows that someone's opinion counts in heaven is worthy of a beracha!" smiled the Satmar Rav. "Pray tell, how you would know such a thing."

The young man told how, as they were almost liberated, he and a friend ran in search of food to feed their starving brethren. The Nazis caught them both and hanged his friend immediately.

"They would have hanged me too on the spot, except that I had done some favors for a few officers and they decided to at least grant me one final wish as thanks for my good deeds. I asked to be able to see my mother one last time and to say goodbye. At first they protested that the women's camp was too far and it would take too long, but finally they agreed. They took me to her and as I stood there before her, I said goodbye, explaining that they were going to kill me. My mother fainted on the spot. As they were taking care of her to revive her, she came to and whispered to me, ‘You will live! You will live!’

“I was dragged away by the Nazis and as they led me to the gallows, the American forces attacked and began to rain heavy artillery and bombs on the camp. The noise and explosions caused the Nazis to flee for cover and I escaped. Later, when the American officers liberated us, I was reunited with my mother. I asked her how she knew I would live. She told me that when she fainted, she rose up before the Heavenly tribunal and saw many Tzaddikim with long beards and hadras ponim (radiant countenances). She did not recognize any of them till she spotted the Satmar Rav, whom she recognized from her childhood in Rumania. ‘Rebbe, Rebbe, save my son!’ she cried to him, ‘Have mercy.’

‘Do not worry,’ said the Satmar Rav, ‘he will live.’ Then she woke up."

So saying, the young man turned to the Satmar Rav and said, "You see, Rebbe, my mother told me how your opinion counts in heaven and I am living proof!"

"Well said,” smiled the Satmar Rav – and gave him his beracha.

(Yiddish Licht Vol. 33 No. 8 Kislev 5742, pages 9-12)

Rav Yitzchok Hutner, Ra”m of Chaim Berlin and author of Pachad Yitzchok, used to say that the Satmar Rav was able to see with a far-reaching vision, greater than many other Rebbes and Rabbonim, saying, "He sees further than all of us."

He once told the following story which demonstrated this far-reaching vision:

Once, two messengers arrived from Eretz Yisrael to visit the offices of Agudas Yisrael in America. They told how recently, many missionaries had been traveling from village to village and from city to city, attempting to turn Jews away from Yiddishkeit toward Christianity. The Rabbonim in Eretz Yisrael asked the Rabbonim of the Agudah to sign a letter of protest against these missionary activities, which would then be sent to the Israeli prime minister, protesting the missionaries’ nefarious activities.

Rav Moshe Feinstein and Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, as well as Rav Hutner and Rav Kalmanovitsh and others discussed the issue, wrote up such a letter and protested vehemently against what was going on. They decided to enlist the help and support of the Satmar Rav as well, thinking that perhaps he too would sign the letter.

Two important Rabbonim acted as messengers and visited the Satmar Rav in his home, asking him to sign the letter and pledge his support in protest against the missionary activities in Eretz Yisrael.

The Rav read the letter and answered them, "I cannot sign this letter." The Satmar Rav then offered the following explanation as to why he would not sign:

"I know that in the next few days the Israeli prime minister has a trip scheduled to Italy. Surely he will take the opportunity to visit the Vatican and meet with the Pope.

“Once he receives this letter, I believe that he will take it with him, show it to the Pope and use it as a tool to find favor in the pontiff's eyes. He will wave our letter of protest and say to the Pope, ‘See – they asked me to intercede against missionary activities, but no – even though Israel is a medina for Yidden, we believe in freedom of religion, and each religion has the right to practice unhindered and teach its ideas to anyone. See – even though the American Rabbonim protest against me, we – the Israeli government – pay them no heed and do not listen to them.’"

The Satmar Rav concluded and said, "I believe the Israeli prime minister will take this letter to the Pope and thereby cause a great Chillul Hashem (desecration of Hashem’s name) – and so I cannot sign a letter which will be used in such a way."

The messengers thought that the Satmar Rav was simply pushing them off with excuses. They did not believe that what he said was true, nor did they take it seriously at all. The letter was signed, sealed and delivered to the Israeli prime minister without the Satmar Rav's signature.

A few weeks later, they all saw just how prophetic the Satmar Rav's words were; they all came true – not one word was false. The prime minister of Israel took the letter with him to the Vatican, showed it to the Pope and the entire episode became public news. Then we all understood that a Divine spirit of intuition spoke through the Satmar Rav, and through his Torah and righteousness he had the power and foresight to see what would indeed happen.

Rav Yitzchok Hutner concluded, "Der Satmar Rav hot gezen far ois mit a pur chodoshim vus es vet zayn– the Satmar Rav saw a few months ahead what would be!" (Moshiyan Shel Yisrael II, page 20)

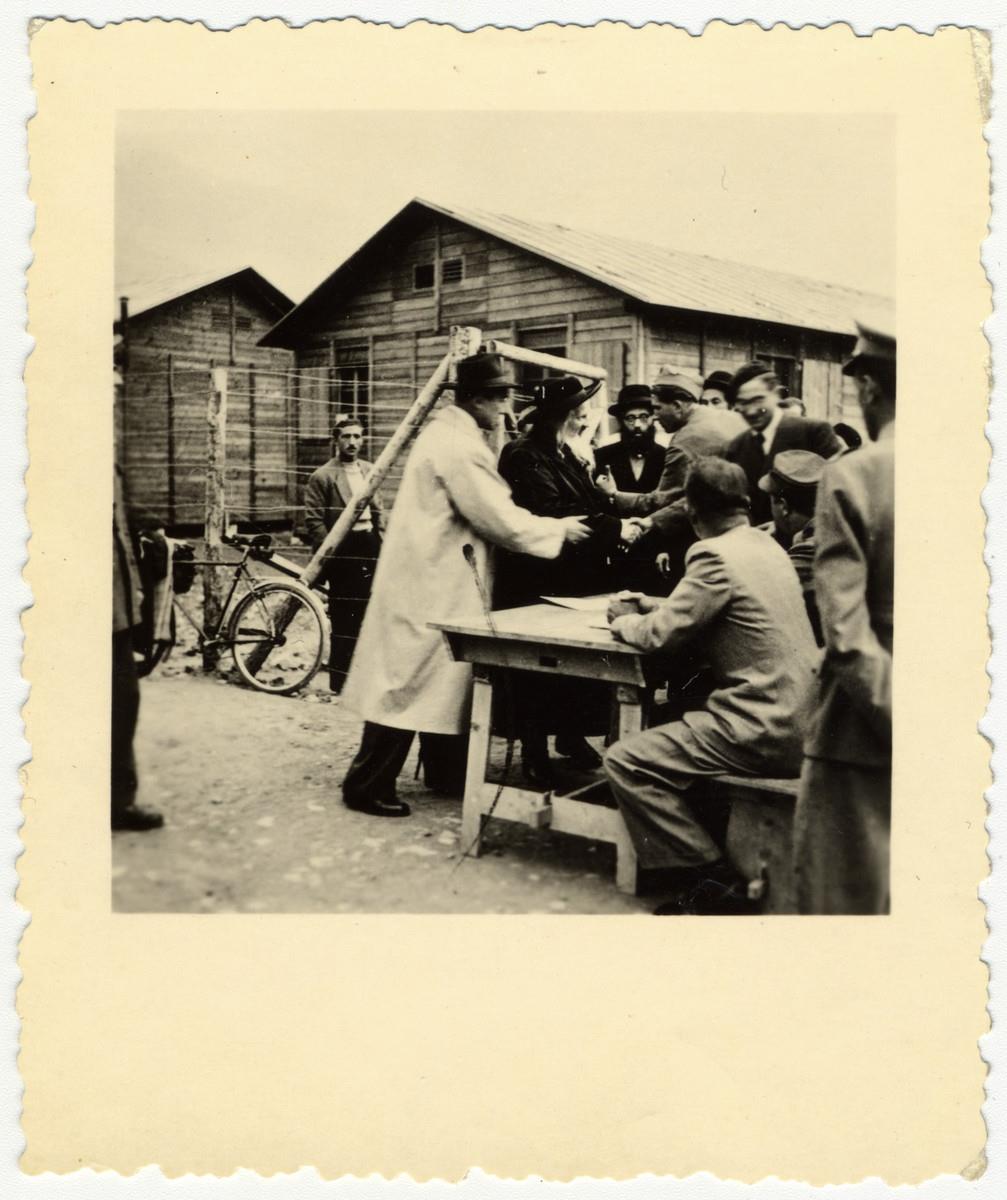

This following article about Rav Yoel Teitelbaum zt”l, the Satmar Rov, was written in 1959 in the Yiddish publication called Das Vort by a Hungarian writer, Dr. Ferenz Kennedy, who was together with the Rov in the famous train of Jewish Hungarian personalities who, by virtue of Rudolf Kastner’s bribery, were taken to an internment camp in Bergen-Belsen, and then later were saved by being taken to Switzerland. Dr. Kennedy was also together with the Rov in Bergen-Belsen, and published this article in the Hungarian newspaper, Oj Kelet, when the Rov was visiting Eretz Yisroel. It was written by an estranged Jew and is of particular interest.

I should start by noting that I am not one of Rabbi Teitelbaum’s followers, but perhaps I can contribute to portraying this unusual person by describing my experiences with him over a period of several months in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where we were confined at a time and place that revealed a person’s true personality.

Rebbe Teitelbaum Fifteen years ago, on July 2, 1944, I first met the Satmar Rebbe at the Hungarian-Slovakian border in Madiarovar, where our train was stopped for two days. A decision had to be made about whether our transport train should travel to Auschwitz, Poland or to Auschpitz, Austira. This was the most important decision for the transport director to make. Each of us understood the difference between Auschwitz and “Auschpitz”….

Someone in our group heard from the conductor that his directive was to travel to Auschwitz. This meant that the transport train was heading to the Auschwitz extermination camp. You can just imagine how desperate we were when we found out about this.

In the meantime the transport train cars moved over to the sidetracks, and we spent two full days inside those cars in an area of three meters on the sidetracks. Along the side of the tracks we noticed a Jew with a nearly gray beard whose face made an enormous impression upon me. Both of his alabaster-white pointer fingers were inside his white vest while he was pacing ack and forth, murmuring his prayers or melodies, moving around like a wounded lion. I do not know whether he was reciting psalms or was thinking about our awful fate. I just saw that he was very upset, moving a few steps among the others with his head bowed. When I asked one of my friends about this man, he replied with certainty, “He is the Satmar Rebbe, Rabbi Teitelbaum! And whoever is with him most certainly has a lot of worries.”

I had never heard of a rabbi like him. The world of the Orthodox religious Jews was foreign to me, and I had never before heard of any Satmar rabbi. Therefore it was no surprise that as a skeptic I could not imagine how people could be so sure that because the rabbi was with us, we had every hope of surviving our Hell. However, I later realized that our hopes were totally justified.

The Hungarian police started approaching the train cars, but the S.S. ordered them away. During those dramatic hours, Dr. Kastner in Budapest intervened. Finally our train was redirected to “Auschpitz” instead of to the Auschwitz death camp. Auschwitz was supposedly filled, and therefore we were sent to Bergen-Belsen.

I lived with the Satmar Rebbe for five months in Men’s Block E in Bergen-Belsen. I do not know how this happened, but it is a fact that the Germans themselves permitted him to keep his beard, which the rebbe concealed with a kerchief around his face, pretending to be suffering from a toothache.

The rebbe did not eat the camp food. He lived on water and cooked potatoes. As far as I know he fasted two or three days a week. You could hear his voice in the barracks almost all day lon. It was not talking we heard, but his prayers and studying. He had a mournful tune and sobbing gestures that kept many of us awake late into the night. I learned those gestures myself, and for years I could hear it in my head as a sad memento of those tragic times. The rebbe’s mournful tune made many of those living in the barracks nervous, but not me. I knew that the rebbe was using that tune to pray to G-d for mercy; he fought against the decree and prayed for rescue.

The Satmar rebbe was crystal clean even in the dirty barracks — dirt and vermin had no power over him. He used to lay on his bed, and his wife and his attendant, a young skinny man, devoted themselves to him, helping him to have something to eat so he could continue with his religious activities.

His majesty and wonderful appearance amazed everyone. I admit that I too was affected by his influence and appeal. There, among the barbwire, the shadow of the Angel of Death was greatly weakened, and I began believing in heavenly forces. I often noticed that whenever Rabbi Teitelbaum recited his prayers, or whenever he simply sang his wordless tune, all of our eyes were filled with bloody tears.

On one summer day, I asked the rabbi’s young attendant to obtain an autograph from the rebbe. The answer came quickly: the rabbi did not consider my request to be appropriate. The weeks passed, and the Satmar Rebbe patiently and modestly suffered and got through the difficulties. However, I once saw him lose his patience. It was when on a Sabbath afternoon when he was deep in study together with Rabbi Shlomo Zvi Strasser of Debrecin. The Satmar Rebbe’s eyes sparkled, and the 90 year-old Rabbi Strasser yielded to the strong will of the Satmar rebbe.

I subsequently became very close to the Satmar rebbe, and this happened as follows:

I had the opportunity to win the trust of a few S.S. men through some bribery and got along with them very well. In exchange for the bribes I gave them, I received newspapers, and the S.S. provided Goebbels’ newspaper, Das Deutsche Reich, as well as the Völkischer Baobachter, the Pressburg newspaper Grenzbote, and other German newspapers. In addition, the German S.S. men would occasionally bring me bread and medicine. Howver, the newspapers were the most important item, and wre our intellectual food. In the camp the newspapers were very significant for us. We frequently derived encouragement from the various news reports, and awaited liberation.

We disseminated the news reports every evening in to barracks among the detainees, and for that purpose the famous Hungarian Jewish playwright, Bela Zholt provided his commentaries and opinions on the dry news that the camp consumed with great curiosity. This is how we found out about the Allied invasion of Normandy. We heard the news about the capture of Warsaw and Paris, and we also learned about hte unsuccessful assassination attempt on Hitler.

One night the Satmar Rebbe sent his attendant to me to ask a favor: since the Rebbe’s bed was far from mine, he could not hear the news reports that were being read in low tones. In addition, the rebbe did not lie in bed at the same time as the other detainees, therefore he requested me to give him the news before I informed the rest of the barrack. I was more than happy to agree to his request, and each evening at 6:30 I would go over to the rebbe’s bed and report to him the most important news and political events. The rebbe closely paid attention and heard the news about the Allied victories with cold indifference and apathy. He commented that “we still need great mercy from Heaven to be able to be liberated from here alive.”

The High Holy Days were approaching, and soon it would be Yom Kippur. Several of the barracks held prayer services, and in our barrack the Satmar Rebbe led the Mussaf service of Yom Kippur. Bela Zholt and Aladar Komlosh (two famous Jewish Hungarian novelists who were also interned in Bergen-Belsen) passed by outside. I approached them and invited them to listen to the prayers of Rabbi Teitelbaum, which was a deeply touching experience to see the rebbe wrapped in his tallis [prayer shawl], rocking back and forth with all his limbs and pouring out his soul to his Creator.

A few meters away, S.S. men were standing outside guarding the camp prisoners in the camp surrounded by barbwire, while inside we could hear the heartbreaking prayerful voice of the Satmar rebbe who was expressing age-old laments of the ancient Jewish prayers.

When we left the barrack, the cynical and assimilated Bela Zholt, who despite being so assimilated had tears welling in his eyes, said to me, “This is quite traditional, but it’s very nice!”

Aladar Komlosh replied that if any prayers existed in the world, it was this true prayer service of the Satmar rebbe. We all felt we were listening to a holy Jewish prayer, and we could not remain indifferent to it.

At the end of November we heard reports that we would be liberated, and would be taken to Switzerland. Our hearts were filled with nervousness, fear, and apprehension. Our minds were filled with doubts as to the veracity of the reports, and the entire camp was in a tense mood.

We got ready to pack our bags and waited for the moment liveration would arrive. On that very day, filled with physical and emotional stress, the rebbe’s attendant approached me and asked whether I still wanted the rebbe’s autograph. Some five months had already passed, and we have lived through many difficulties. I had already forgotten about the whole subject. “Of course I would like to have the rebbe’s autograph,” I replied with a restrained smile.

This is how I obtained the rebbe’s autograph in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. The rebbe had not forgotten about the subject of my request during all those months, and as soon as it became “appropriate” he fulfilled my request.

Afterwards, when we were actuaally released and in Switzerland on one cold December night, we marched along St. Galen Street to the barracks that had been prepared for us. On the corners of the street we were met by fellow Jews who were unable to approach us up close, but tossed apples and sweets our way, and we caught them with both hands. However, these Jews who threw us gifts had one question: “Where is the rebbe?” Bela Zholt strode along side me, excitedly observing, “You see, Ferenz, I am nothing! No one knows me even though hundreds of thousands of people have read my novels and poetry. No one is waiting for me; they only know the rebbe. They are only waiting for him!”

Our group comprised more than 1,300 people, including various famous personalities from the Hungarian Jewish community. The majority of our group was of course assimilated and modernized Jews. There were very few Orthodox Jews. The transport comprised professors, poets, artists, community activists and leaders of the Hungarian Zionist movement and their families. The Satmar rebbe, Rabbi Teitelbaum, did not at all fit in to our community, whose major leaders were intellecuals and academics who believed that as soon as liberation arrived, they would be greeted with great honor. Yet suddenly here they were so bitterly disappointed since here in Switzerland almost no one paid any attention to them. EVeryone was interested in the personality known as the Satmar rebbe, Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum. Everyone wanted to know where he was in the transport, and how he was feeling. Everyone asked the same question: Where is the rabbi?

So we all realized that it was not the professionals and academics who were indispensable, but rather the quiet and haggard holy man.

In Switzerland we all parted ways, but for a long time thereafter until today, I think a great deal about the fascinating personality of the Satmar rebbe. I frequently still remember the following little philosophical ideas:

When we consider the significance of religion, and the fact that the Torah and faith is what has preserved the Jewish People over thousands of years of Exile, we must also realize that the Satmar rebbe is without a doubt one of the holiest individuals produced by the Jewish People, and is the greatest guardian to assure that the Torah of Moses is not forgotten, G-d forbid. It may be possible that we perceive him as being too fastidious, too stubborn about following every point of the Torah, but without a doubt he is the real and most loyal defender of the Torah, a true leader of the Jewish People!

Segulos of Rav Yoel Teitelbaum zt"l

There is a segula to help wayward offenders return to the fold, this segula was often prescribed by the Arader Rav and Rav Aharon Fisher. It is found in the Degel Yehudah of the Stretiner and Rav Hirschele Miller's version with detailed instructions is found here. The Segula is to write their names on bricks and to bake them erev Shabbos with the Challos in the oven and recite three times that just as these bricks baked and burned in the oven so should the heart of Ploni ben Ploni - insert Hebrew Name son of Mother's Hebrew Name burn with the fire and passion for avodas Hashem and then bury it in the kever of a well known famous tzadik or next to the kever of a tzaddik, many do so by the kevarim of the Kasua Rav of Williamsburg Tolaas Yaakov, by the kever of the Ohr haChaim haKadosh, by the kever of the Divrei Yoel of Satmar or Ribnitz or by the kever of a Tanna. Rav BenTzion Mutzafi and Rav Shmueli also prescribed this segula to others to do to help people repent and do teshuvah see https://www.doresh-tzion.co.il/QAShowAnswer.aspx?qaid=27591