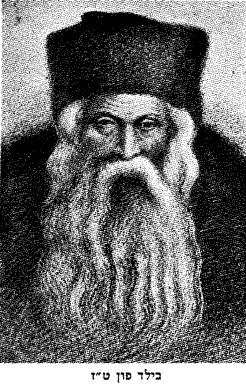

Rav Dovid HaLevi Segal zt"l

הרב דוד בן שמואל סגל זצ"ל

Shevat 26 , 5427

Rav Dovid HaLevi Segal zt"l

Rav Dovid, the son-in-law of the Bach, was born in Ludmir and was the unofficial Rav of Posen, 1619~1640. Rav Dovid headed the famous Yeshiva at Ostroh from 1643, escaped the Cossacks’ rampage of 1648–49 to Lublin, then went to Moravia. He settled in Lemberg (Lvov) but lost two sons to violent deaths in the spring pogroms of 1664. He sent his son Yeshaya and son-in-law Aryeh Leib (later to be the Sha’agas Aryeh) to investigate Shabsai Tzvi. He also wrote Divrei Dovid on Rashi al HaTorah.

Rav Dovid’s family was famed for scholarship. His father, Rav Shmuel, was the son of the famous scholar, Rav Yitzchok Betzalels. He had an older half-brother called Rav Yitzchok HaLevi, a great Talmud scholar, who founded a Yeshiva in Vladomir, Chelm and Lvow, Poland, and was the mechaber of two books on Hebrew grammar, called Siach Yitzchok and Bris HaLevi. This great man dearly loved his younger brother, and became his first teacher and counselor for many years. The affection between the two brothers never diminished in later years, and they continued to correspond with each other in writing after they had been separated. A part of this correspondence has been preserved. These letters are of great interest not only because they testify to the deep friendship and love that existed between the two brothers, but also because they contain an exchange of scholarly opinions on many problems of Jewish law. In addition to his scholarship, Rav Dovid’s father was well-to-do, so that the young prodigy Dovid, who had shown unusual talent for study, was fortunate enough to grow up in an atmosphere of both wealth and learning. His early, happy youth was in marked contrast to his later years, when he suffered great hardships and poverty, as we shall see later. He became a reputed Talmudic scholar, and married Rivka, the second daughter of Rav Yoel Sirkes of Brest, mechaber of the famous commentary on the Tur, Bayis Chodosh (whom the Taz frequently quotes in his works). He was also a mohel. As was customary in those days, Rav Dovid stayed in his father-in-law’s house for several years, during which he applied himself fully to the study of the Talmud and Poskim (codifiers). This period served as a good preparation for the great contribution which he himself was to make to this immense literature.

After continuing his Torah studies for several years, he left his father-in-law’s house to make a home of his own, moving to Cracow. He was then appointed chief Rav of Potelych (Polish: Potylicz), near Rava, where he lived in great poverty. Later, he went to Poznań, where he remained for several years. Around 1641, he became Rav of the old community in the famed city of scholars, Ostroh, (or Ostrog), in Volhynia. There, the Taz established a famous Yeshiva, and was soon recognized as one of the great halachic authorities of his time. In Ostroh, the Taz wrote a commentary on Rav Yosef Caro's Shulchon Aruch (Yoreh De'ah), which he published in Lublin in 1646. This commentary, known as the Turei Zohov ("Rows of Gold"), was accepted as one of the highest authorities on Jewish law. Thereafter, Rav Segal became known by the acronym of his work, the Taz. He accepted the position of Rav in a small town, a position he changed several times for other small towns. During this time he suffered poverty and want, and was stricken by other misfortunes also. Several of his children passed away in infancy, but overall Rav Dovid HaLevi enjoyed a peaceful period of teaching and writing.

However, the Taz and his family had to flee the massacres of the Cossack insurrection under Bogdan Chmielnicki in 1648–1649. They were fortunate enough to leave Ostroh before it was captured by the Cossacks. He also succeeded in saving his priceless manuscripts. Rav Segal went to Steinitz near Ostrog, Moravia, where he remained for some time. Not happy in Moravia, he returned to Poland as soon as order was restored, where he was invited to become Rav of Lvov (Lemberg), and remained there for the rest of his life. In Lemberg, Rav Segal was appointed Av Bais Din (head of the rabbinical court). When Rav Meir Sack, chief Rav of Lemberg, was niftar in 1653, he succeeded him in this position as well. However, a cruel blow was struck at the aging Rav when, three years before his death, in the spring of 1664, he lost his two older sons, Rav Mordechai and Rav Shlomo HaLevi, who were murdered in a pogrom in Lemberg. His wife had passed away long before; now Rav Segal married the widow of her brother, Rav Shmuel Hirz, Rav of Pińczów. His third son from his first marriage, Rav Yeshaya, and his stepson, Rav Aryeh Leib, were the two Polish scholars who were sent — probably by Rav Segal, or at least with his consent — to Turkey in 1666 to investigate the claims of the pseudo-Messiah, Shabsai Tzvi.

Most of Rav Segal's works were published long after his petira. The Turei Zohov was published by Shabsai Bass in Dyhernfurth in 1692. The work is subtitled Mogen Dovid ("Shield of Dovid", after Rav Segal's first name) in many editions. Both commentaries (Taz and Mogen Avrohom), together with the main text, the Shulchon Aruch, were republished frequently with several other commentaries, and still hold first rank among halachic authorities. Two years before the publication of this work, Rav Yudel of Kovli, in Volhynia, a mekubol and Talmudic scholar who wrote a commentary on Orach Chaim, gave money to have it published together with the Taz. His wishes were never carried out, but his money was used to publish another of Rav Segal's works, Divrei Dovid ("The Words of Dovid"), a super-commentary on Rashi (Dyhernfurth, 1690). Rav Segal also authored responsa which, though sometimes quoted from the manuscripts, were never published. He and Shabsai Kohen (the Shach) are among the greatest halachic authorities among the Acharonim. In 1683, the Council of Four Lands declared that the authority of the Taz should be considered greater than that of the Shach, but later the Shach gained more and more in authority.

His commentary on the Shulchon Aruch was so well-respected and esteemed that many of the leading Rabbonim began to use his opinions, decisions and rulings as the basis for their own. This roused the ire of other Rabbonim such as Rav Shmuel Koidinover, mechaber of Birchas HaZevach, and Rav Gershon Ashkenazi, mechaber of Avodas HeGershuni, who felt that it was improper to rely on the decisions of such later authorities over deciding the case through the earlier works. They felt that the commentaries of the Taz and his contemporary Rav Shabsai Kohen, mechaber of the Shach, were full of errors and mistakes.

Just as earlier in history, the Maharam Lublin had attacked the Shulchon Aruch and the Rema for what he saw as shortcomings, and was ignored, so were the attackers of the commentaries on Shulchon Aruch ignored. Their opinion was in the minority and the majority of the Rabbonim greatly respected and followed the rulings of the Shach and Taz to the point where today, no Rav can earn semicha without having studied and mastered their commentaries in addition to having studied and mastered the Shulchon Aruch and the Rema.

[According to the Shu”t Shoel Umeishiv they opened the kever of the Taz, one hundred years after his petira and found him in perfect condition – even his clothes had not decomposed. (Brought in the Shem Gedolim of the Chida)].

Stories of Rav Dovid HaLevi Segal zt"l

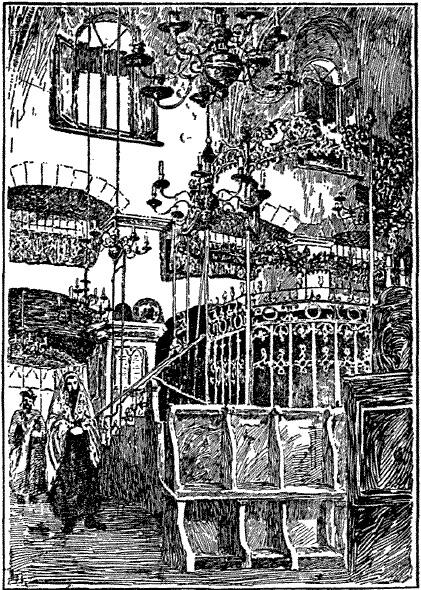

The Taz wrote about his personal tragedies in his commentary, the Turei Zohov (see comments to Orach Chaim, end of Siman 151, the laws of the shul). “In my youth, when I lived in the holy community of Cracow, my home and personal house of study where located above the shul (this is a frowned-upon location as indicated by the Shulchon Aruch, ibid) and I was greatly punished when my children died and I pointed to this as the cause of their untimely death.” Later, he was appointed as Rav of several cities, including Lwów.

[According to the Shu”t Shoel Umeishiv they opened the kever of the Taz, one hundred years after his petira and found him in perfect condition – even his clothes had not decomposed. (Brought in the Shem Gedolim of the Chida)].

In his commentary to Pirkei Avos 1:1, Ruach Chaim, Rav Chaim of Volozhin tells us the following story: “The story is told regarding our master Rav Dovid, the Gaon and mechaber of the commentary Turei Zohov (Taz on Shulchon Aruch) that once a woman came before him, crying and shouting, ‘Woe is me! Rebbe, behold my son is so weak he is at death’s door!’

“He answered her, ‘Am I in Hashem’s place?’

“She responded: “I am calling out to the Torah which you learn and represent! For the Holy One and His holy Torah are one and united!’

“And he answered her, ‘I will do this for you: I will give as a gift the Torah which I am studying now together with my students for your sick son; maybe in its merit he will recover and live, since the pasuk says: ‘With this [Torah] shall you live a long life,’ and at that moment his fever broke. We see that through Torah study, with the power of his dveikus, attaching himself to Hashem, one has the ability and merit to revive and resurrect the dead!”

The Taz was well known as a miracle worker. Once the daughter of a wealthy householder in Levov had taken ill and the Taz was asked to visit her and pray for her recovery. He agreed, and when he arrived and opened the door the girl opened her mouth and exclaimed "Baruch HaBah! Welcome!," and she immediately turned to face the wall.

When the Taz asked her why she had turned away? She answered that the wicked cannot look at the face of the righteous Tzadikim, and that “In Heaven you are called, 'Our master and Rabbi the author of the Turei Zahav.'” He answered her, "If this is true, I hereby decree that you should be healed immediately through the merit of my Torah study. For today I sat and studied a difficult and wondrous passage in the Tur and I answered the difficulty in the true manner of Torah." And so she was cured. This was recorded in the ledger of the Levov community records.

(Shem haGedolim HaShalem Chida Kuntres Shatz p118)

The Ta”z was often an innovator and his novel rulings in Halacha often had a global impact on customs that today we take for granted. For example in Europe during the Taz's lifetime kosher wine was often hard to come by and often very expensive. This lead to the question of whether one could use Sheychar – Beer or Whiskey or Yayin Seraf – Brandy in lieu of wine for kiddush. The Shulchan Aruch itself discusses this question, but there were several differing opinions quoted. The question is even more appropriate to the Kiddusha Rabbah – the kiddush recited Shabbos morning which is an enactment of the Rabbis rather than of Torah origin. Based on the realities of hardship and poverty the Taz ruled that: “In a place where there is to be found wine, surely one must recite kiddush over wine even during the day. However if the wine is expensive as it is in our countries we do not act stringently and use wine, since it is not a complete obligation as it is during the kiddush at night. This is why even the greatest of the sages among us did not have the custom to recite the blessing over wine during the day. However whoever does pronounce the blessing [of kiddush] over wine during the day surely is acting in a proper and meritorious fashion.”

Source: (Orach Chaim Hilchos Shabbos Siman 272 Taz #6)

I heard from the Rav of Nalivitz who heard this from someone who read it in Prozhina's town ledger. When the Taz was the Rabbi of Prozhina he was extremely poor. His poverty was so great that he could not afford to heat his meager home in the cold winter nights. He would study Torah all night long and the bitter cold would seep into his bones. Not far away was a tavern and sometimes he would visit to have a drink to strengthen himself and warm his frozen spirit allowing him to continue learning and studying Torah. Since he was too poor due to his meager salary to pay up front, the bar man gave him credit by writing what the Taz owed him on the wall of the bar. Many locals also frequented the tavern, and when one day one of them noticed the Rabbi's name on the wall he asked the bar man what it meant. When he heard that the Rabbi bought spirits on credit, the man was astonished to think that the Rabbi drank at all! One friend has another, and pretty soon all the local tongues began wagging with exaggerated tales of the Rabbi's drinking and debts. He was voted out of office and the town had him removed with great dishonor on the wagon used for refuse.

Afterwards when the Taz became the Rabbi of Ohstrah and he began to print his magnum opus the commentary Turei Zahav on Shulchan Aruch, the price of wine rose, since there was a shortage of grapes in those environs. The Taz innovated that whiskey and brandy should also be considered fit for kiddush. However he wrote a condition that in Prozhina this was not the case since they all hate brandy and whiskey The Taz wrote this in utter sincerity since he truly believed that he was removed from office for drinking something the townspeople considered unbecoming for the Rabbi and that spirits must be considered poor and tasteless in those parts!

When the townspeople of Prozhina heard about the Taz's rulings they immediately called together an assembly and urgently met to discuss the issue since it greatly hurt them financially. They decided to send a prestigious delegation to Ohstrah to meet with and ask for the Taz's forgiveness. The Taz's home was located above the Beis Midrash and when heavy footfalls were heard on the stairs leading up, all the Taz's household assumed it was the householders of Prozhina since they wore heavy boots.

When the delegation came before him they all asked his forgiveness in the name of the entire town as was the law and custom. The Taz asked them to be seated and had the Rebbetzin honor his guests with some cakes. When he noticed that they had not touched the food he asked them why? The Prozhina delegation searched for a proper way to broach the issue of the spirits and here was the opportunity. “Why how can the Rav set cakes before us without something to drink? Everyone knows that the primary form of refreshments is the drink! And the cake is but an added delicacy to flavor the spirits!” They then explained that this was their principle reason for visiting the Taz. “The honorable Rav wrote that one can recite kiddush over spirits except in our locale since we hate them. And this is not true rather we like them very much however it was not our desire that our Rav would be a drinker.” They asked him to change his ruling and the Taz had it erased from his work Turei Zahav. (Kisvei Rav Yoshe # 12 p135)

Rav Dovid HaLevi Segal also known as the Taz because of his work the Turei Zahav on Shulchan Aruch was quite poor. His paltry earnings and monthly wages as the Rav of the city left him without any extra money besides what he had to purchase the bare necessities. However he never complained about his lot, in fact the only thing that caused him suffering was his inability to purchase any new seforim from which to learn.

One day a seforim salesman arrived in town with a wagon of new seforim for sale. As was the custom he displayed the books on tables in the beis midrash so that clients would be able to see them and study them before making a purchase. Rav Dovid was delighted to see so many seforim. He opened and studied them one after another, but to his dismay all of them were well known to him and he had studied them all at one time or another. The salesman who noticed that Rav Dovid was looking and searching for something asked the Rav, "I have a new volume, a sefer of great importance that I have not yet placed on the table due to its expensive price.

However if your honor is interested I can take it out and let the Rav take a look at it?" "What is the name of this sefer?" asked Rav Dovid. "This is the sefer HaAgudah whose author Rav Alexander Zuslin Katz sanctified Hashem's name and died the death of a martyr many years ago. Till now his sefer was unavailable except as a handwritten manuscript. However just recently it has been printed and published." Rav Dovid had heard of the sefer but had never actually seen nor studied it. He asked the salesman to be allowed to look at the sefer.

After the salesman took out the newly published volume and Rav David had studied it he realized that it was full of new, novel and innovative Torah thoughts. He decided that he wished to purchase it and inquired after the price. But when he heard the exorbitant sum asked by the salesman he put the precious sefer back down on table in defeat. The asking price was almost as much as his entire monthly salary as the Rav of the town!

"I am sorry I cannot afford to buy this sefer," he explained. The salesman could see the Rav's disappointment and so he offered him a substantial discount, however even with the discount the price was still too much for him to afford. However when he heard that the salesman planned to spend the night in town the Rav had a plan.

"Please," asked Rav Dovid, "would you allow me to borrow this sefer just for tonight and tomorrow I will return it to you?" The salesman agreed happily.

With the Sefer HaAgudah in hand Rav Dovid went home, closeted himself in his room and studied the sefer all night long with no breaks until he had completed the entire sefer by dawn.

He reviewed it and its main points and returned to the Beis Midrash that morning to return the sefer to the salesman.

"Although I was careful to guard this sefer," explained Rav Dovid, "I know that your rely on the sale of your books as a means of livelihood and sustenance for yourself. Please I do not wish to have benefitted from your sefer for free. Allow me to pay you a small fee for having read the sefer."

The salesman was so taken and excited by the Rav's offer that he decided to give the Taz the book as a gift. The Taz however refused his gesture.

And from then on the Taz never saw the sefer HaAgudah again in his life. However he quoted it in his commentary several times all from memory, all based on that one night when he had the opportunity to study and memorize it from the borrowed volume he had on loan. (Masay Avos p31-34)

His commentary on the Shulchon Aruch was so well-respected and esteemed that many of the leading Rabbonim began to use his opinions, decisions and rulings as the basis for their own. This aroused the ire of other Rabbonim such as Rav Shmuel Koidinover, mechaber of Birchas HaZevach, and Rav Gershon Ashkenazi, mechaber of Avodas HeGershuni, who felt that it was improper to rely on the decisions of such later authorities over deciding the case through the earlier works. They felt that the commentaries of the Taz and his contemporary Rav Shabsai Kohen, mechaber of the Shach, were full of errors and mistakes.

Just as earlier in history, the Maharam Lublin had attacked the Shulchon Aruch and the Rema for what he saw as shortcomings, and was ignored, so were the attackers of the commentaries on Shulchon Aruch ignored. Their opinion was in the minority and the majority of the Rabbonim greatly respected and followed the rulings of the Shach and Taz to the point where today, no Rav can earn semicha without having studied and mastered their commentaries in addition to having studied and mastered the Shulchon Aruch and the Rema.

As is well known, the Taz wrote a commentary on the Shulchan Aruch. He was a Rav and Rosh Yeshiva in the big city of Posen in Western Poland, but after a few years decided that he was not cut out for the Rabbinate. He decided to become anonymous by going to the town of Lvov in Eastern Poland, where nobody would recognize him and he would be able to learn in peace and quiet. After a few weeks in this town, someone came over to him in the shul and said, “Rabbeinu.” It turns out it was one of his former talmidim who happened to live in the town. He swore him to secrecy that he would not reveal who he was.

After a few months, the Taz was resigned to find work to support his family. He found work in the slaughterhouse, skinning and cutting meat. A number of shailos came up in the plant. They happened to ask him if he knew what the din was and he paskened a few questions. Word got to the Rav of the town and he was very upset. He called in the Taz and decided to put him in cherem for paskening shailos instead of referring them to the Rav of Lvov. He could no longer learn in the shul but would have to stay in the booth where the guard sat.

One time a young girl came with a question about a chicken to the Rav and the Rav paskened that it was not kosher. The girl ran out crying. The Taz, who was in the booth outside the shul saw her and asked her why she was crying. She said, “My mother is a widow and this means we will not have chicken for Shabbos.”

The Taz looked at the chicken and said, “The chicken is kosher. Go and tell the Rav to look in Yoreh De’ah Siman 18 in the Taz, in footnote 8, and he will see that the chicken is in fact kosher.”

The young girl went back into the shul and told the Rav. The Rav looked up the halocha and then realized that he had made a mistake; the chicken was in fact kosher. He asked the girl, “Who told you this information?”

She replied, “The man sitting outside in the booth.”

The Rav went outside and asked him, “How did you know that Taz?”

“Because I am the Taz!”

The Rav immediately called the entire town together and announced in the shul that he was stepping down as Rav and handing the reigns over to the Taz. The Taz accepted. The student, who had known the whole time of the Taz’s identity, asked his Rebbe, “Why did you reveal your identity and why are you accepting the position?”

The Taz explained, “I really wanted to remain in hiding, but when I saw the tears and felt the pain of this yesoma (orphan), all my personal plans were no longer significant. I had to do something to prevent the pain and anguish to this poor family and any other poor family in the future.”

Rav Yehoshua of Belz (whose Yahrzeit is 23rd of Shevat) used to relate the following story he had heard from his father [the Sar Sholom] about the Taz:

Once, a woman who was having a very difficult time giving birth cried before the Taz to save her life and the baby.

“What can I do to save you? Only this can I offer,” replied the Taz. “Because of the fact that today I answered a difficulty in the commentary of the Tosafos, I hereby give this merit to you!”

As soon as he had spoken, she delivered the baby easily, without any further distress or difficulty.

The Sar Sholom concluded that this is no wonder at all: because the Taz answered a difficulty, easing the understanding of the Tosafos, when he passed on that merit on to her, they eased her difficulty and just as easily did she give birth. (Cited in the name of the Rav of Vilkomin – Chemda Genuza II, p. 30)

The minhag of the Taz was always to recite Kiddush on Shabbos and Yom Tov from the siddur. He explained that besides the kedusha found in the osiyos (letters) themselves, it prevented the embarrassment of others. Many times the Taz found himself a guest among people who were ignorant and did not know to recite Kiddush by heart. The Taz sought ways to avoid embarrassing other Jews, and was sure that if he said Kiddush by heart, they would be embarrassed to recite Kiddush from a siddur. Therefore, he always said it from a siddur and encouraged others to follow his example. (Beis Rochel, Shaar Hachona, by Rav Naftoli Katz #34)

Divrei Torah of Rav Dovid HaLevi Segal zt"l

in the beginning divrei david rashi's father: the entire world belongs to the holy one and he gave us eretz yisroel

Bereshis "In the beginning Hashem created " (1:1)

Rashi's commentary begins: Rav Yitzchak said Hashem did not need to begin the Torah but from "This month shall be for you the beginning of all months," because that was the first commandment with which Israel was commanded. What is the reason the Torah begins with Genesis? To convey the message that "He told the power of His acts to His people," in order to allow them to inherit the nations, so that if the nations say to Israel, "You are thieves since you conquered and stole the land of the seven Canaanite nations." Israel will answer them that, "The entire world belongs to the Holy One, and He gave it to whoever He deems proper. Originally He gave it to them, and then He took it away from them and gave it to us."

The Taz writes in Divrei David that: When I was a young lad I saw a very old hand written manuscript that was a commentary on Rashi. In it was written that this initial statement in the name of Rav Yitzchak, is not found in the Midrash or Talmud. Rather the question itself is found in our Midrash but not in the name of Rav Yitzchak. And that this Rav Yitzchak is in fact none other than Rashi's own father. (Rashi is an acronym for Rav Shlomo Yitzchaki “Shlomo the son of Yitzchak) This Rav Yitzchak was no great scholar and so Rashi wished to honor his father by mentioning him immediately at the beginning of his commentary. So Rashi said ask a question and I shall write it in your name, and he asked Rashi simply, why does the Torah begin with Bereishis? Therefore there is no question why Rashi's commentary seems to ask two questions, since the first question is indeed not his own, but his father's which he wrote to honor him. This is what I read there in that manuscript. However that statement saying that Rav Yitzchak, Rashi's father was not a great scholar is an error. We see that it is false from the fact the Rashi himself in his Talmudic commentary to Avoda Zarah page 75 quotes his father's interpretation as superior, This is what I heard from my father and teacher, who reposes in honor and it seems to me to be correct.